New York Times, November 8, 2018

Headline: How the N.R.A. Builds Loyalty and Fanaticism

Byline: Nicholas Kristof

Another needless tragedy in America: This time a gunman opened fire in a bar in Thousand Oaks, Calif., killing at least 12 people and injuring many more.

These horrors happen far more often in America than in other advanced countries partly because of the outsize political influence of the National Rifle Association. N.R.A. candidates suffered some important defeats in Tuesday’s midterm elections, but in a broad swath of red state America it remains potent, controlling politicians who know that an N.R.A. endorsement can make or break an election.

It is not the richest interest group. The National Association of Realtors has spent twice as much in the 2018 federal election cycle, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

It is not the largest interest group. It claims about six million members (probably an exaggeration); AARP has more than six times that number.

But the N.R.A. attracts incredible loyalty from its members. “That’s the critical thing people miss,” said Robert Spitzer, a political scientist at SUNY Cortland and the author of five books on gun policy. He said that the group combines a shared pastime with “ideological fervor.”

“It’s a layer on top of a hobby,” he said. “It’s bowling plus fanaticism.”

All N.R.A. members receive a subscription to one of the organization’s magazines. We studied one of them, The American Rifleman, for clues about how the N.R.A. spurs its members’ zealotry.

There are newer N.R.A. publications that focus expressly on gun rights. But The Rifleman has been published under its current title since 1923, revealing how the group has politicized and mobilized its members over the past century.

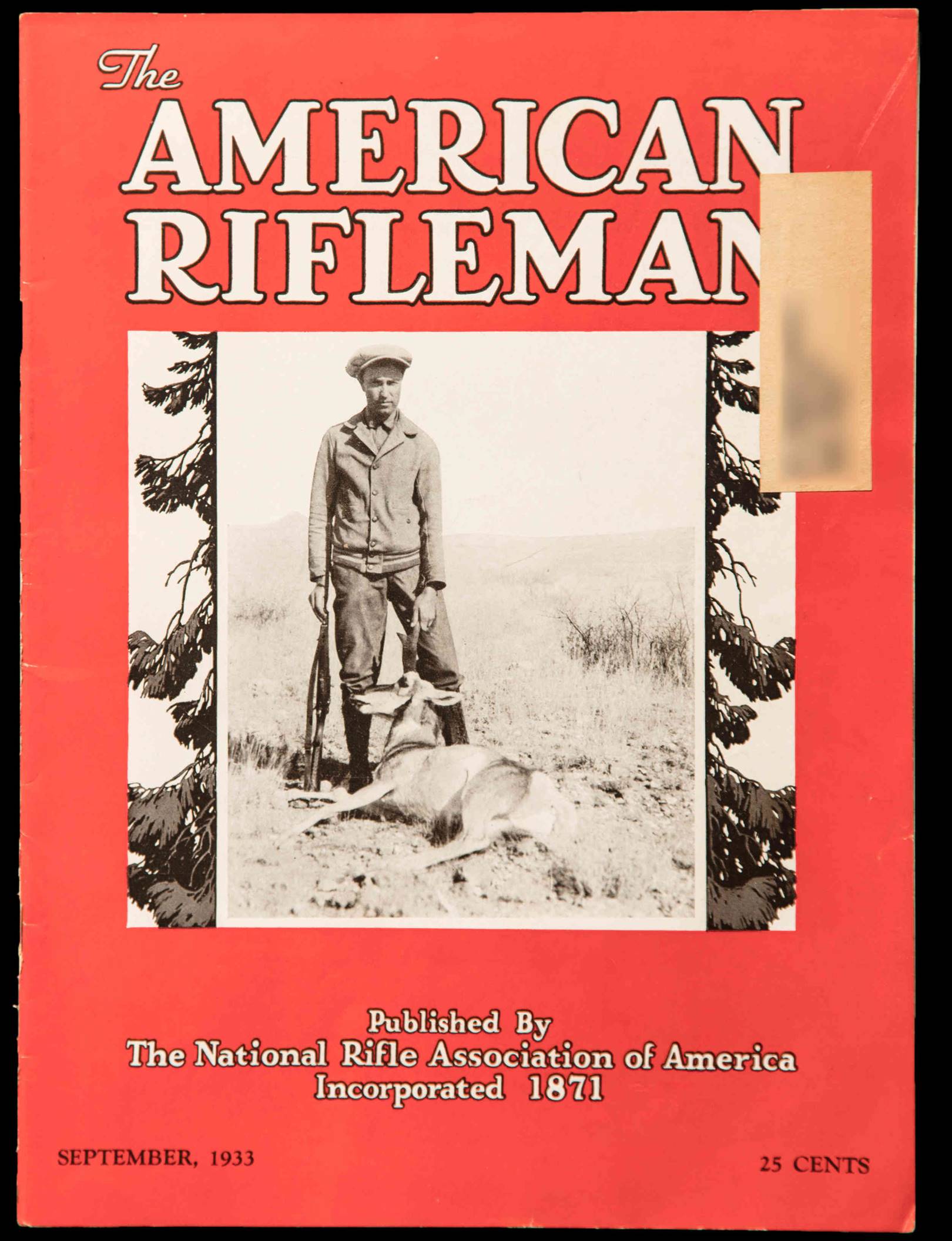

The covers of the magazine show how the N.R.A.’s conception of itself has evolved from a largely apolitical association of hunters and sportsmen …

September 1933

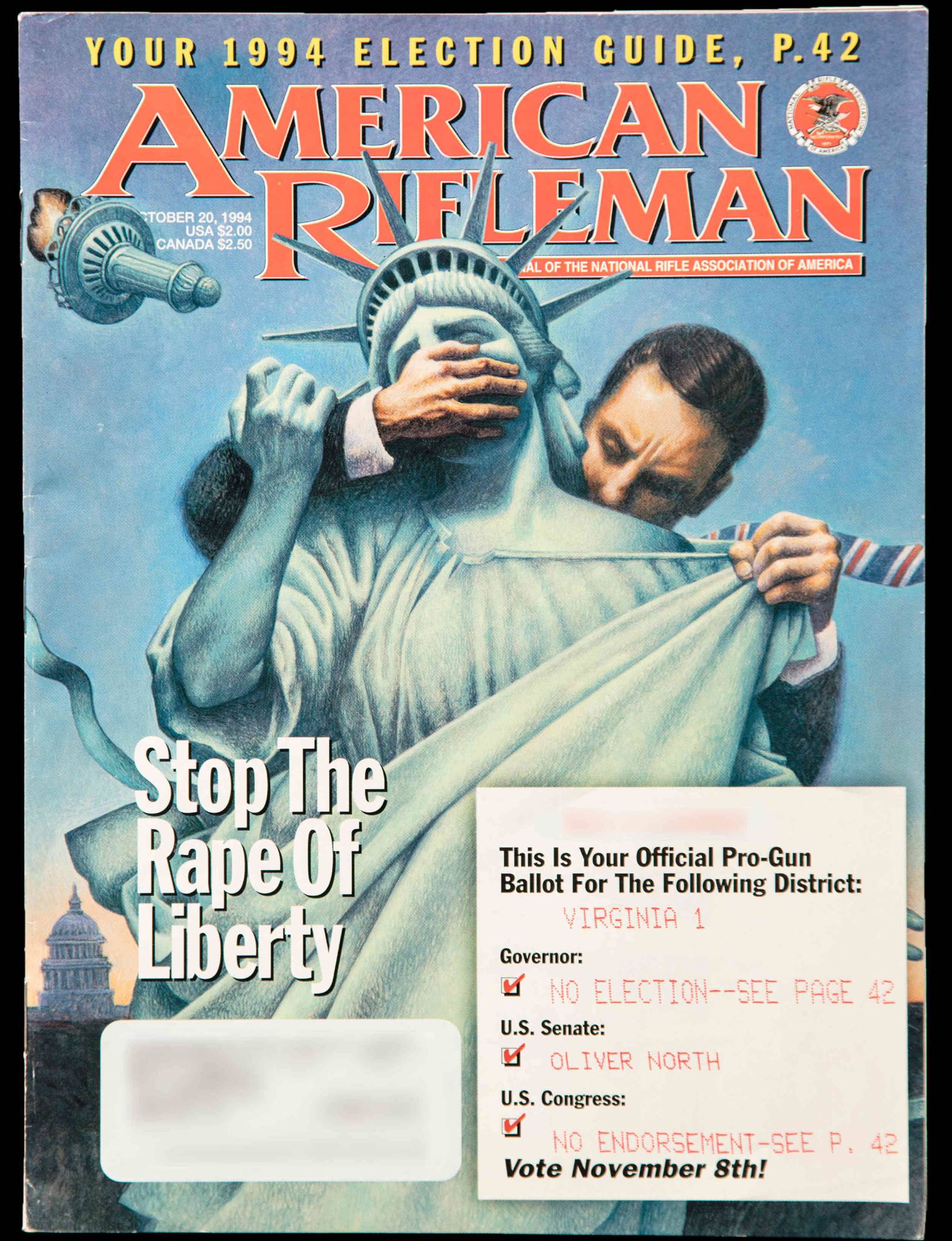

… to the last line of defense against “gun-banning” politicians.

October 1994

Early issues of The Rifleman focused on marksmanship and gun safety. A cover from 1923, for example, questions the importance of “hand-gun fit.” Another from 1959 places “firearms safety” first among the organization’s priorities.

July 1923

May 1959

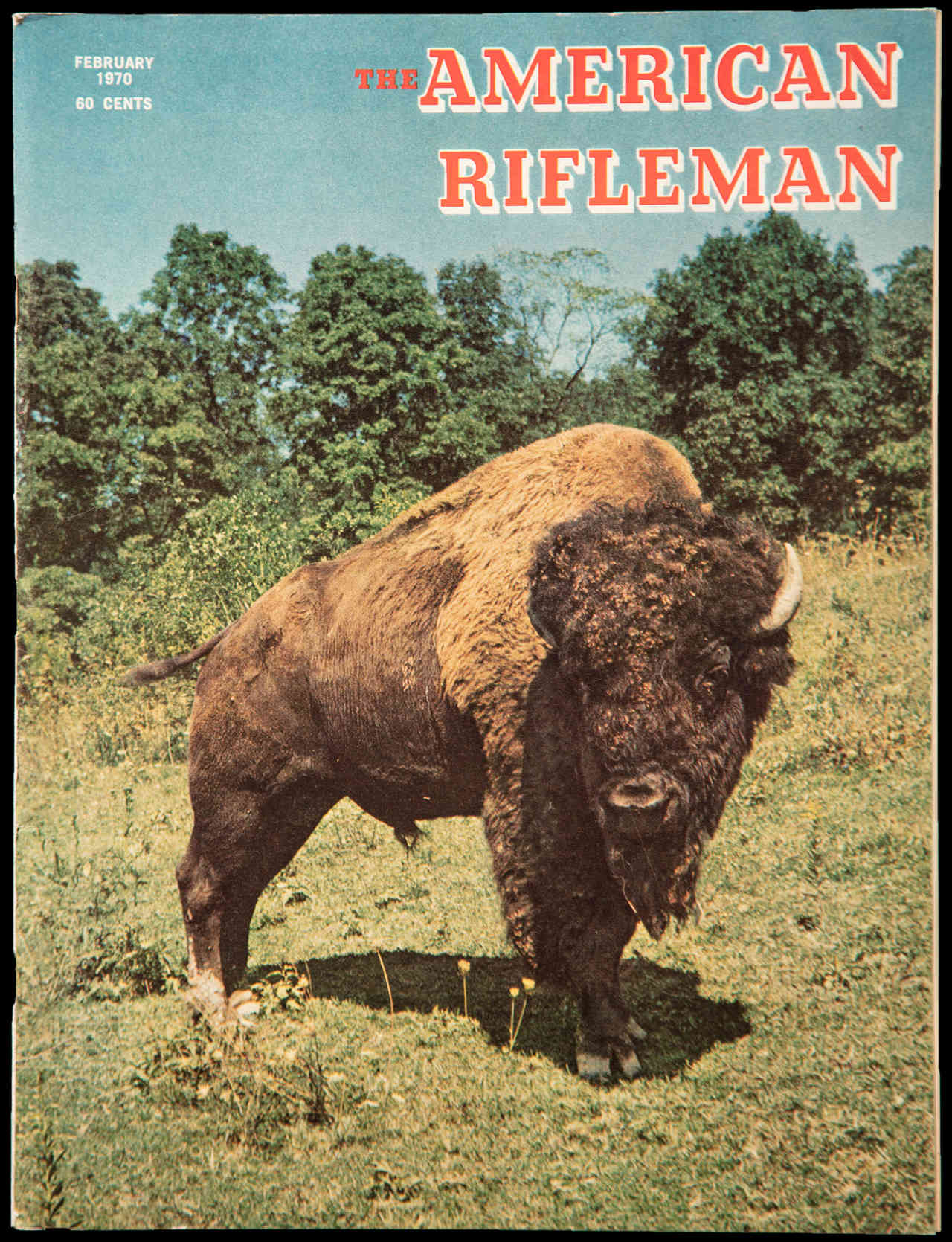

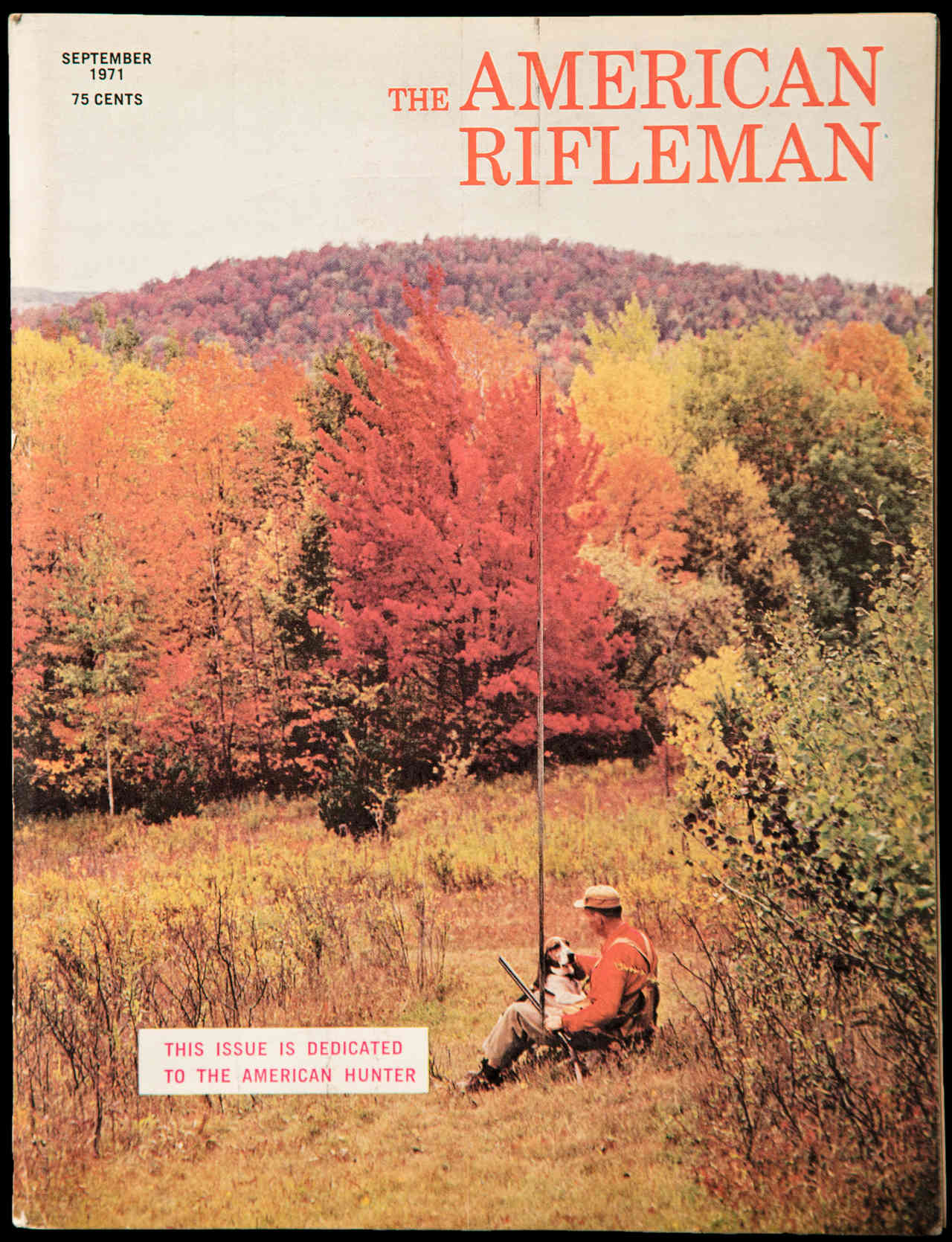

Through the early ’70s, the covers often showed bucolic hunting scenes. Stories about hunting were broken out into a separate magazine, The American Hunter, in 1973.

February 1970

September 1971

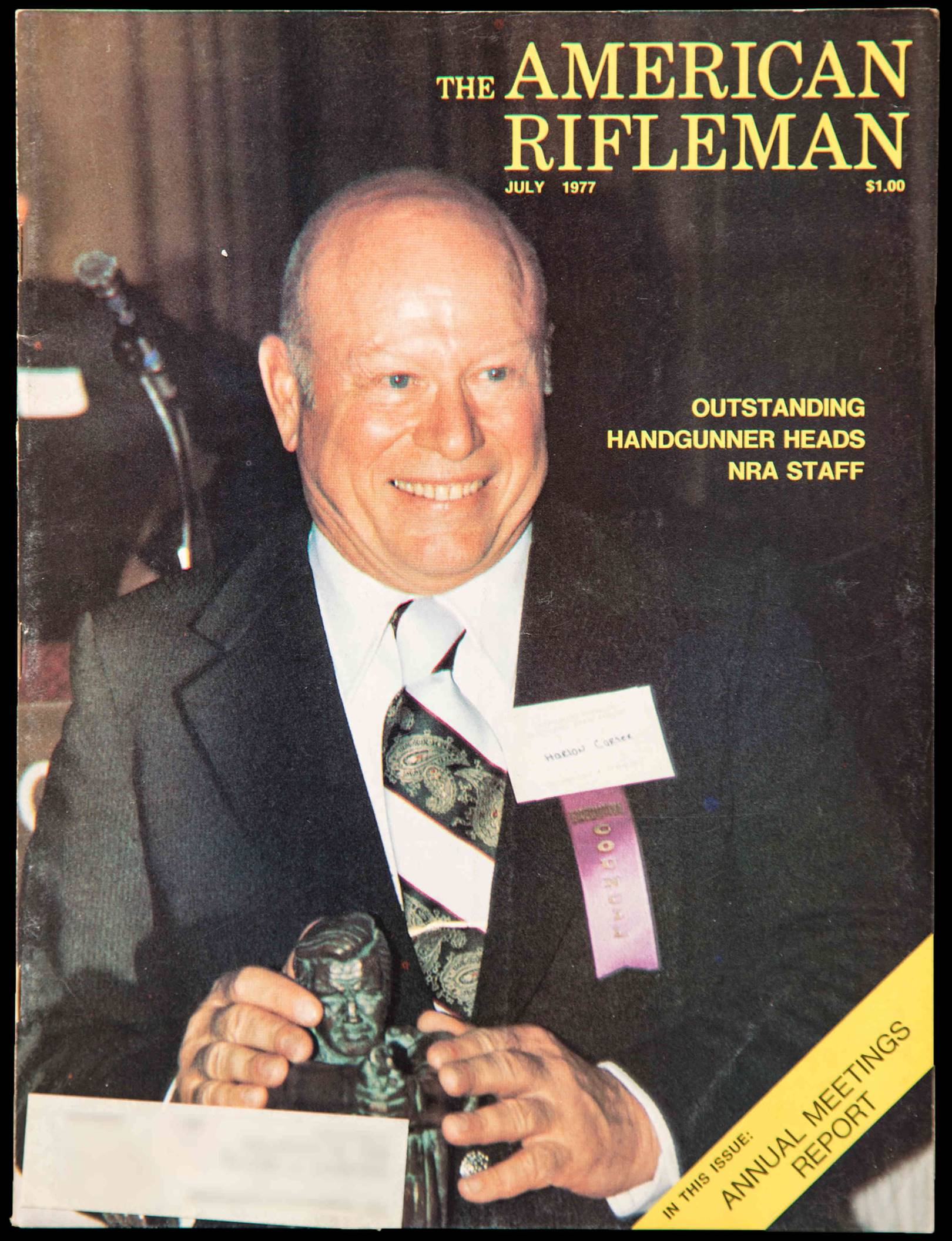

But beneath the idyllic covers of the ’70s was internal strife. A faction of the N.R.A. pushed the group to take a more active role in defending gun rights, and hard-liners staged a coup at the N.R.A.’s 1977 gathering.

They overwhelmed the moderates, who wanted to preserve the organization’s focus on marksmanship and hunting, ousted the leadership and installed Harlon B. Carter to run the organization. He appears on the July 1977 cover.

July 1977

Mr. Carter was a former Border Patrol chief who, in his youth, was convicted of murdering a Hispanic teenager he believed might have committed a crime; the conviction was later overturned on a technicality. After he took charge, the N.R.A. became increasingly focused on individual gun rights, sometimes seeming to embrace the vigilantism that Mr. Carter had embodied as a boy.

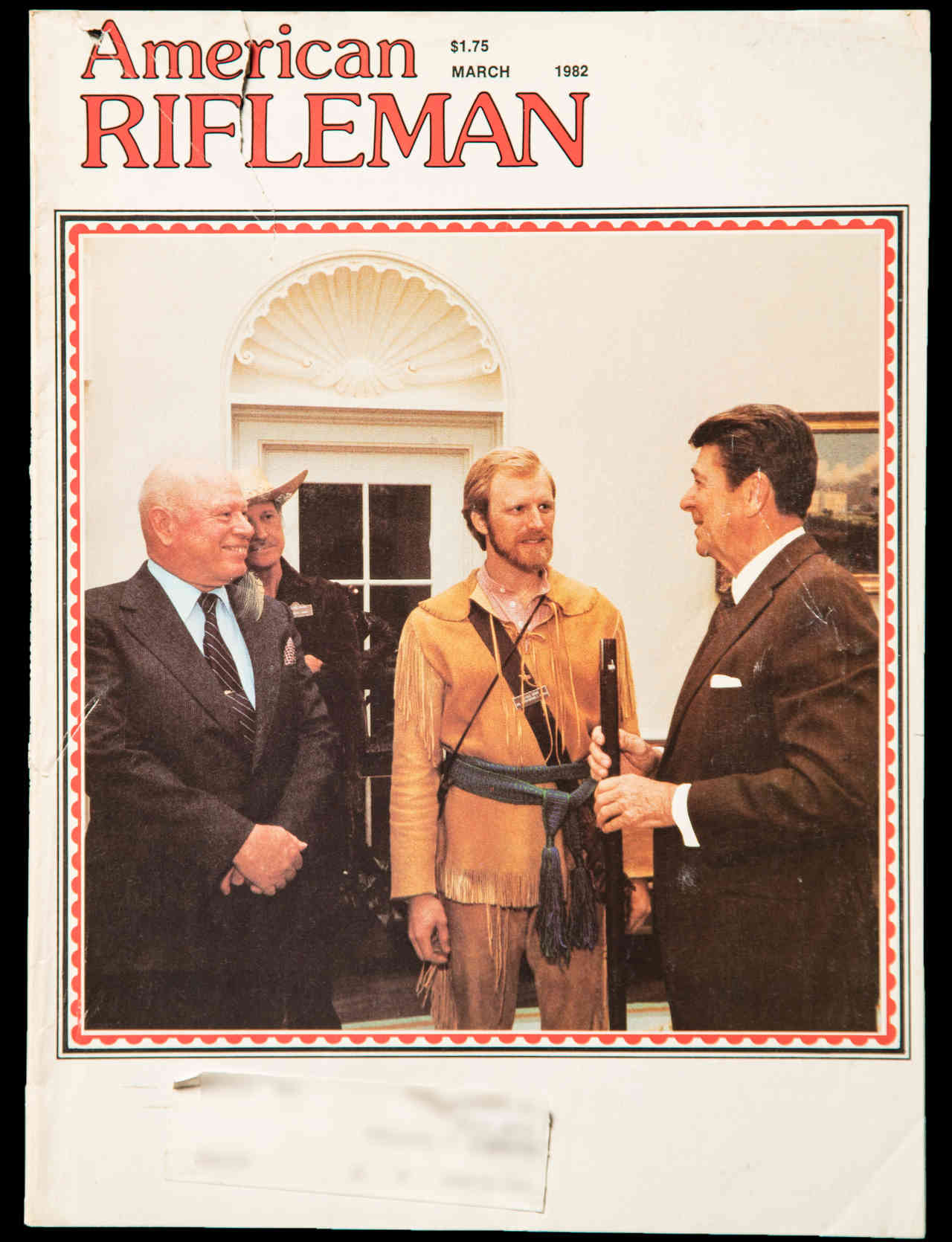

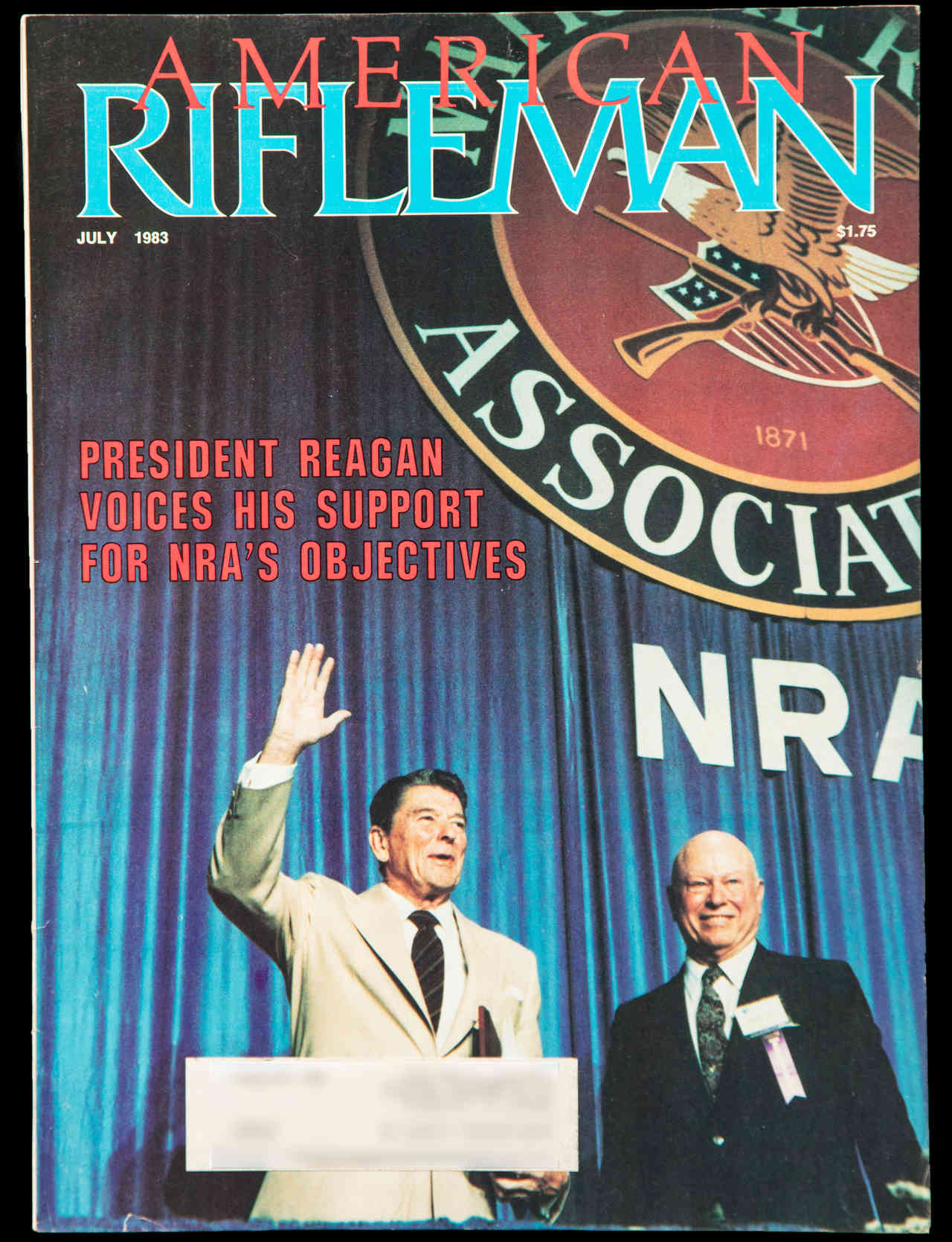

The organization also became more explicitly political. In 1980, Ronald Reagan became the first presidential candidate to receive the N.R.A.’s endorsement, and in 1982, The Rifleman put him on its cover. The following year, Mr. Reagan became the first sitting president to address the N.R.A.’s annual convention, and he appeared alongside Mr. Carter on a 1983 cover.

March 1982

July 1983

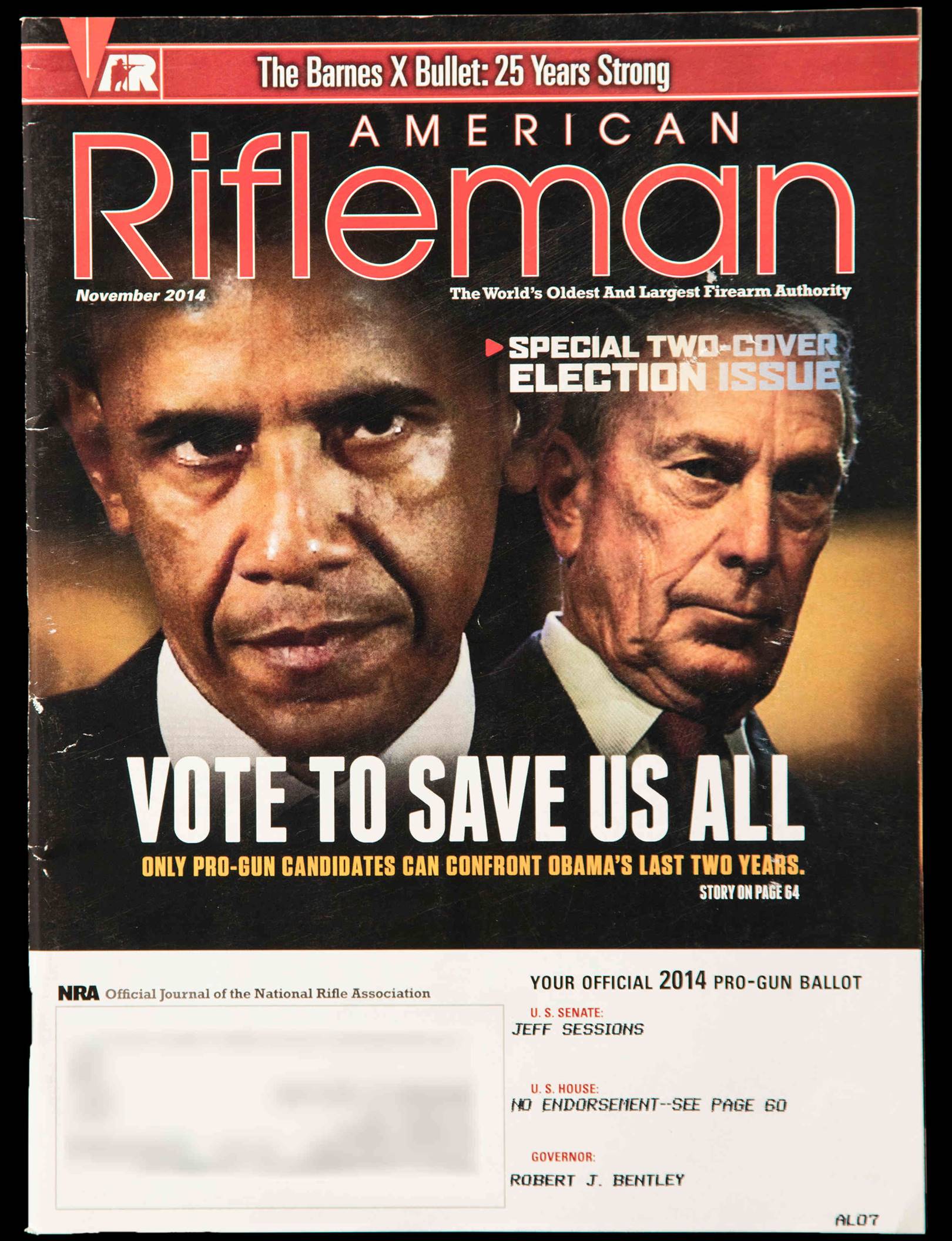

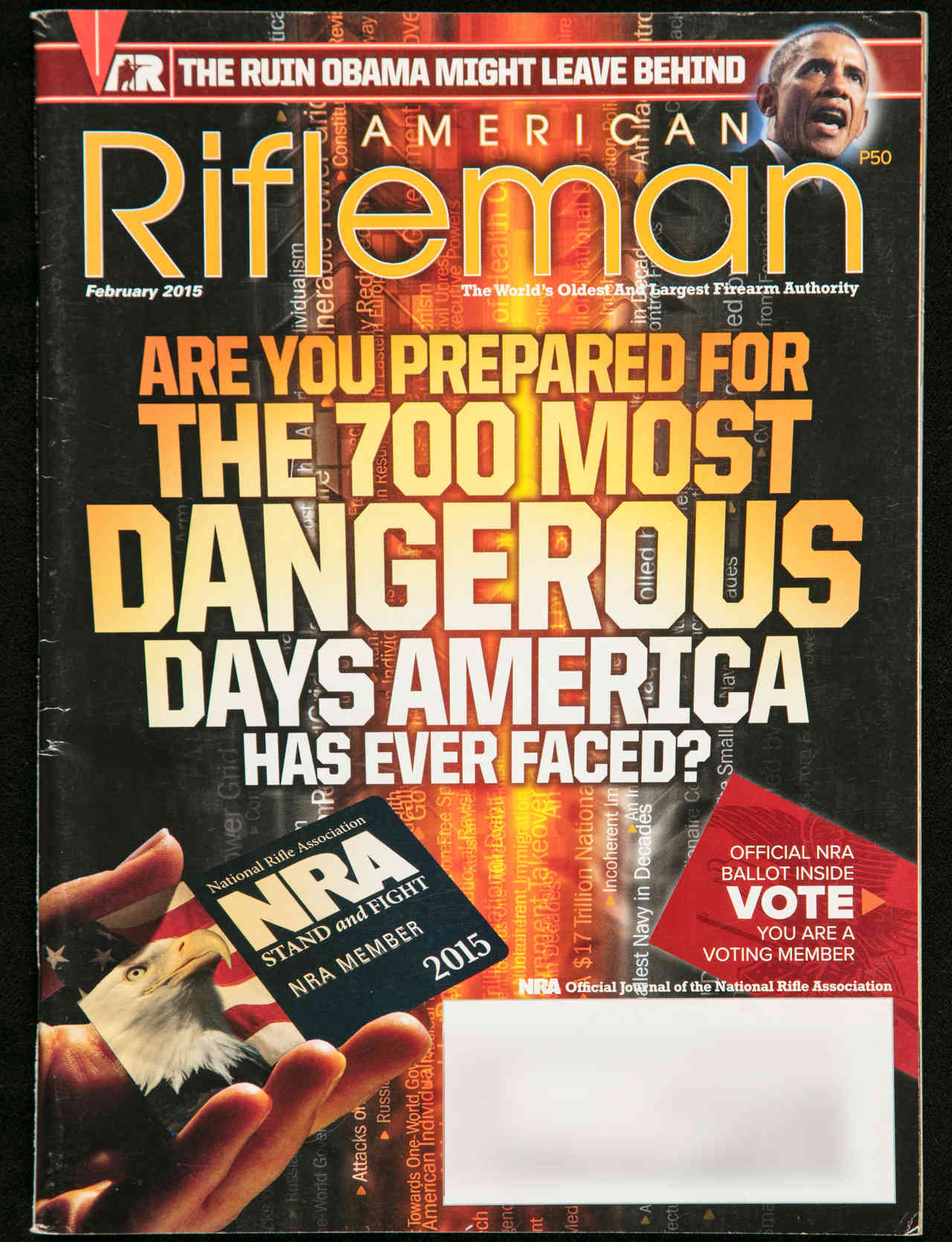

Politicians — especially purported enemies of the N.R.A. like President Barack Obama and Michael Bloomberg, the former mayor of New York — have frequently appeared on the pages of The Rifleman.

November 2014

The N.R.A. mobilizes its supporters by emphasizing threats to gun owners’ rights and values.

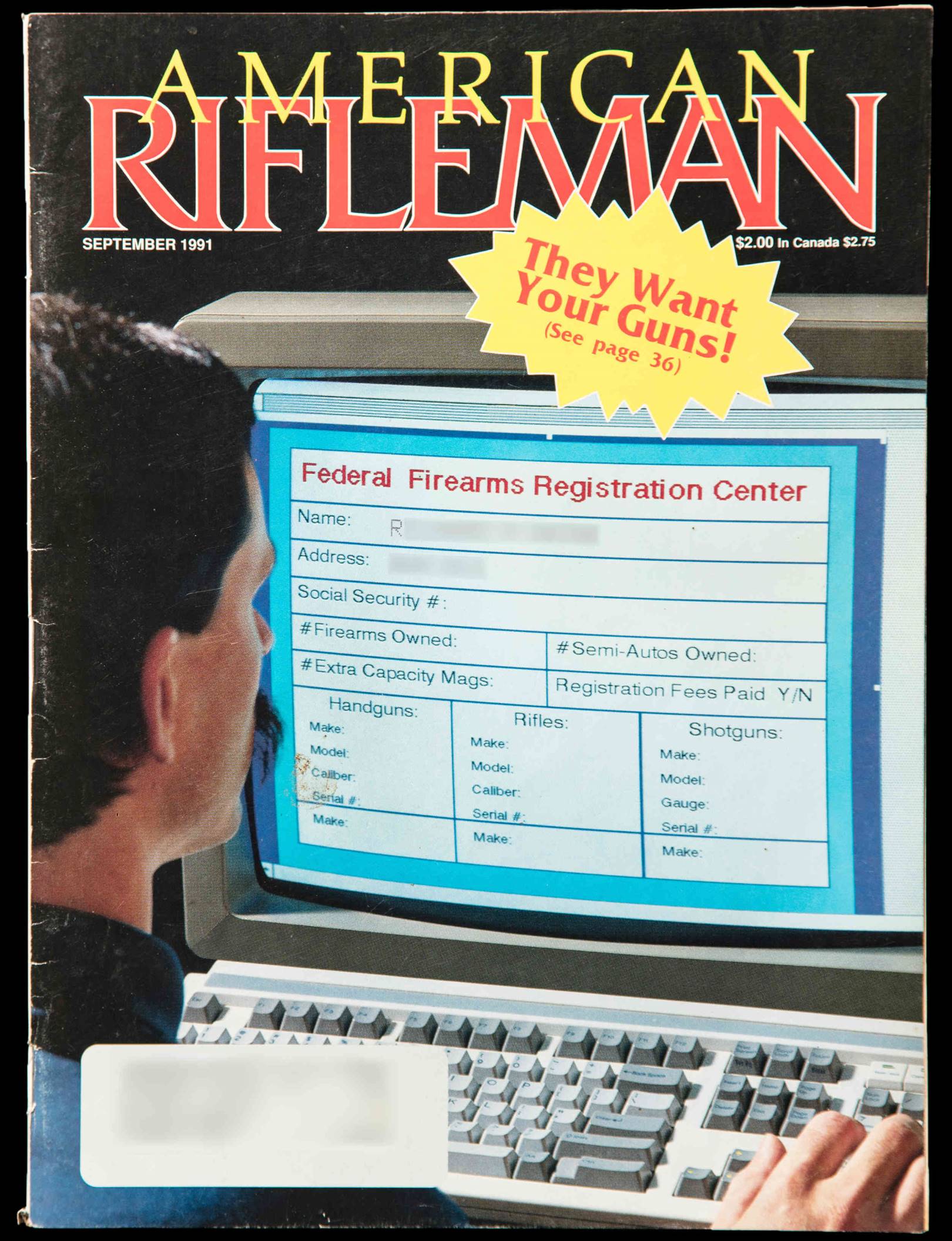

One oft-repeated claim is that the government wants to assemble a database of gun owners to aid future firearm confiscation.

On a 1991 cover, the magazine printed the subscriber’s name and address on a mock “Federal Firearms Registration Center” screen, alongside a callout that warned, “They Want Your Guns!”

September 1991

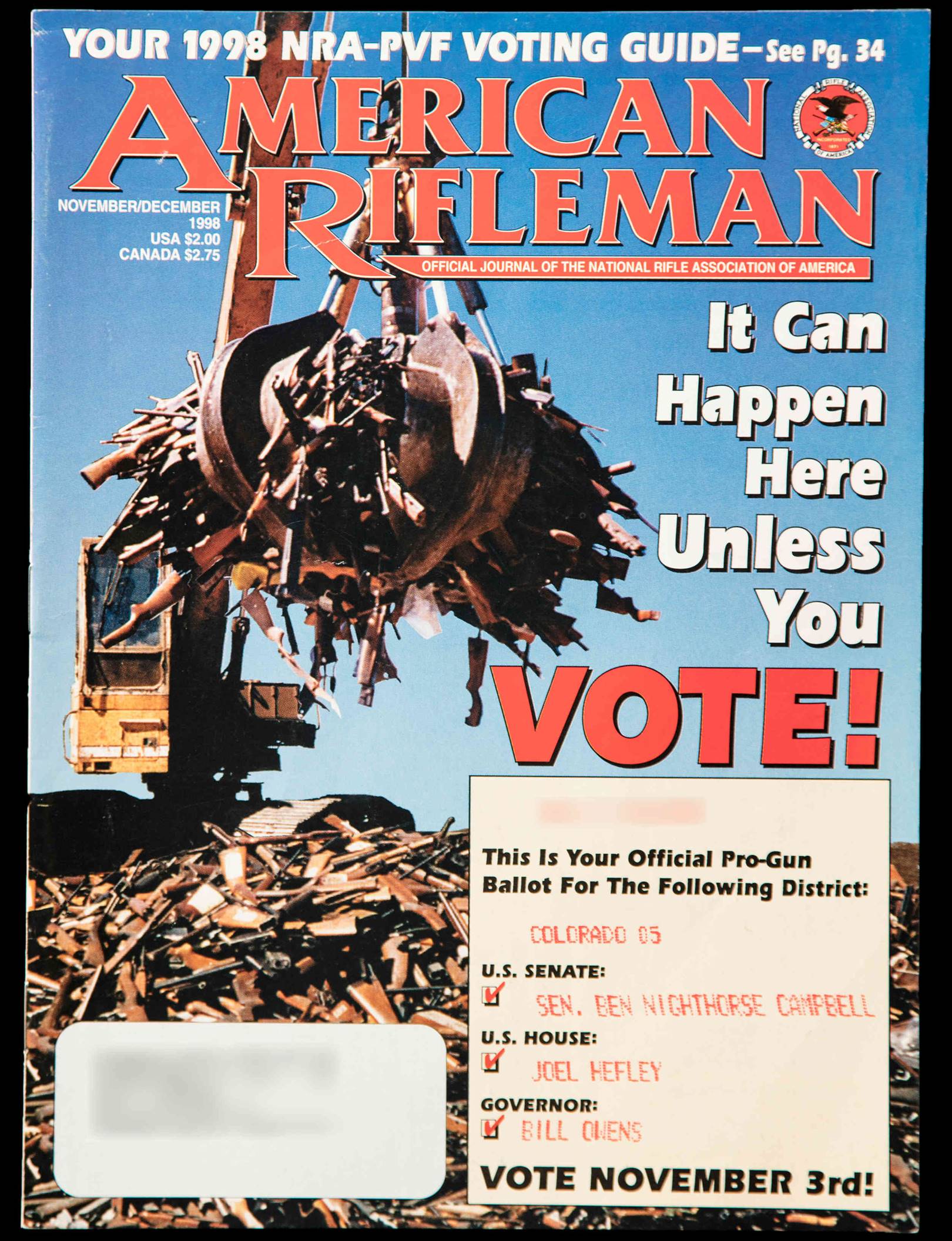

Fear of confiscation also animates a 1998 cover that warns members to vote or risk the same future as Australian gun owners. The photograph shows guns being destroyed as part of a mandatory Australian buyback program.

November 1998

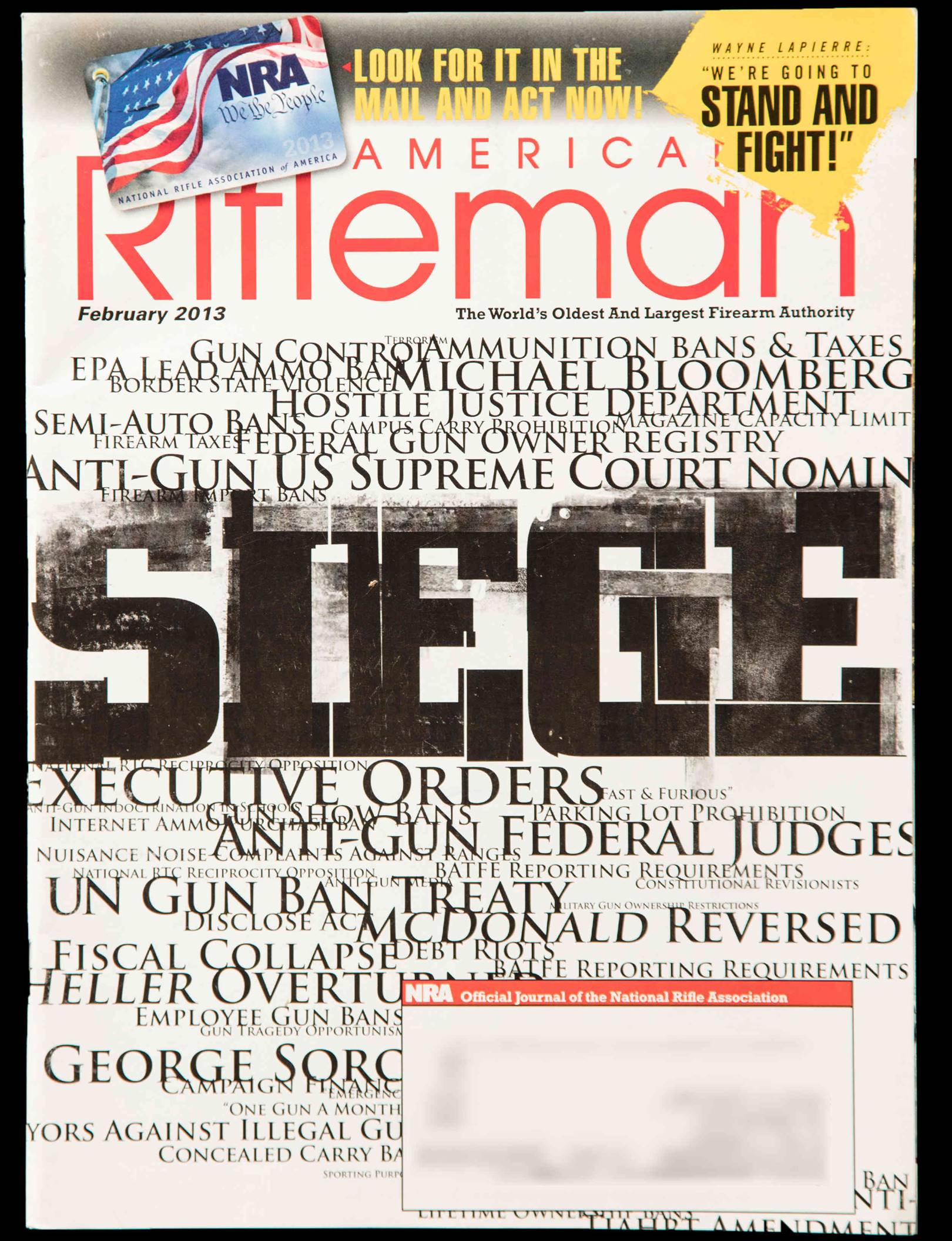

A 2013 cover declares a “siege” and presents a litany of threats: a “hostile Justice Department,” “anti-gun indoctrination in schools” and, simply, “George Soros,” the progressive philanthropist who is a favorite target of right-wing conspiracy theories.

February 2013

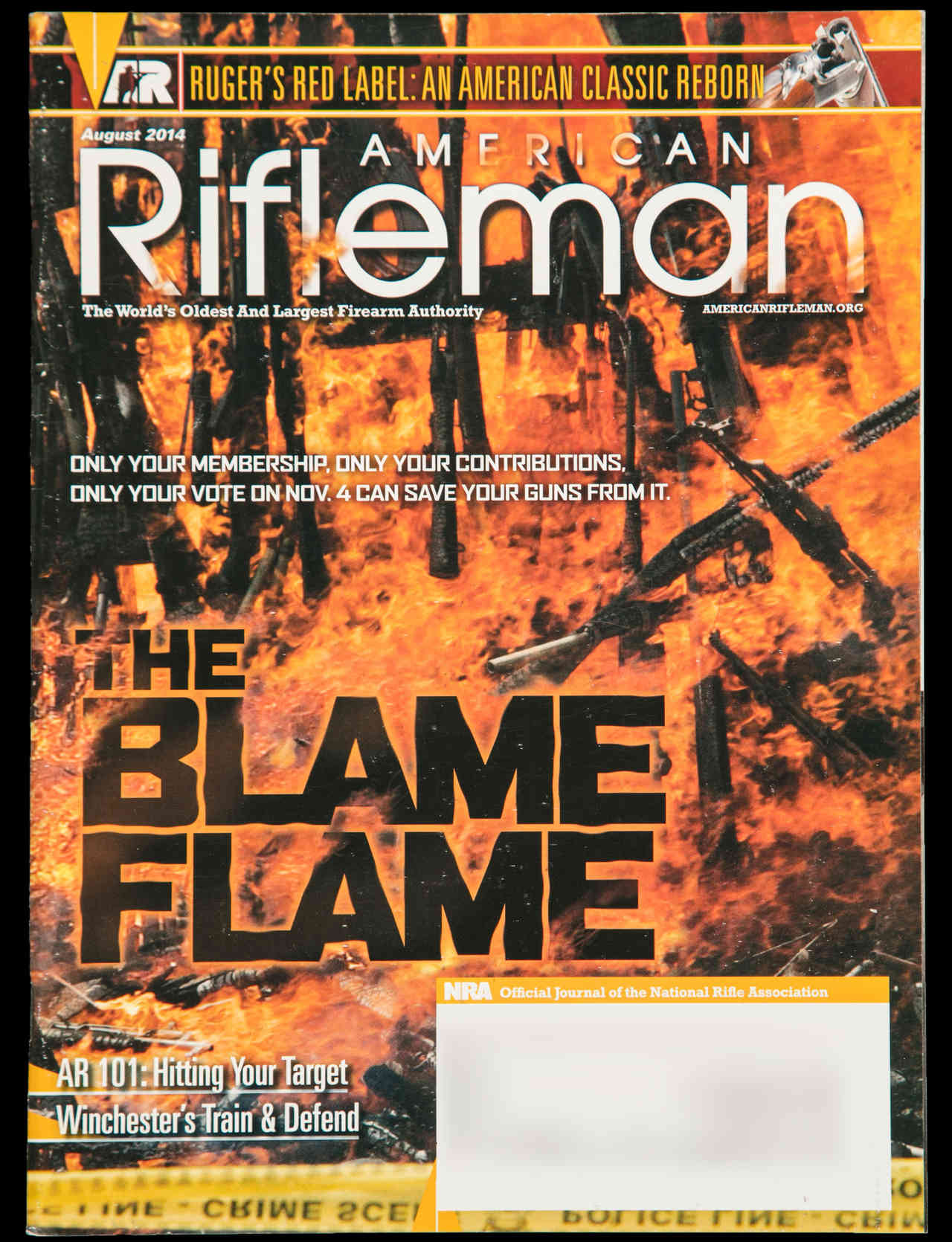

Recent covers have used apocalyptic language and imagery to provoke subscribers.

August 2014

February 2015

.

Though the N.R.A. aligns most often with Republicans, it says its sole priority is defending the Second Amendment, and it will battle politicians from any party who back gun safety measures.

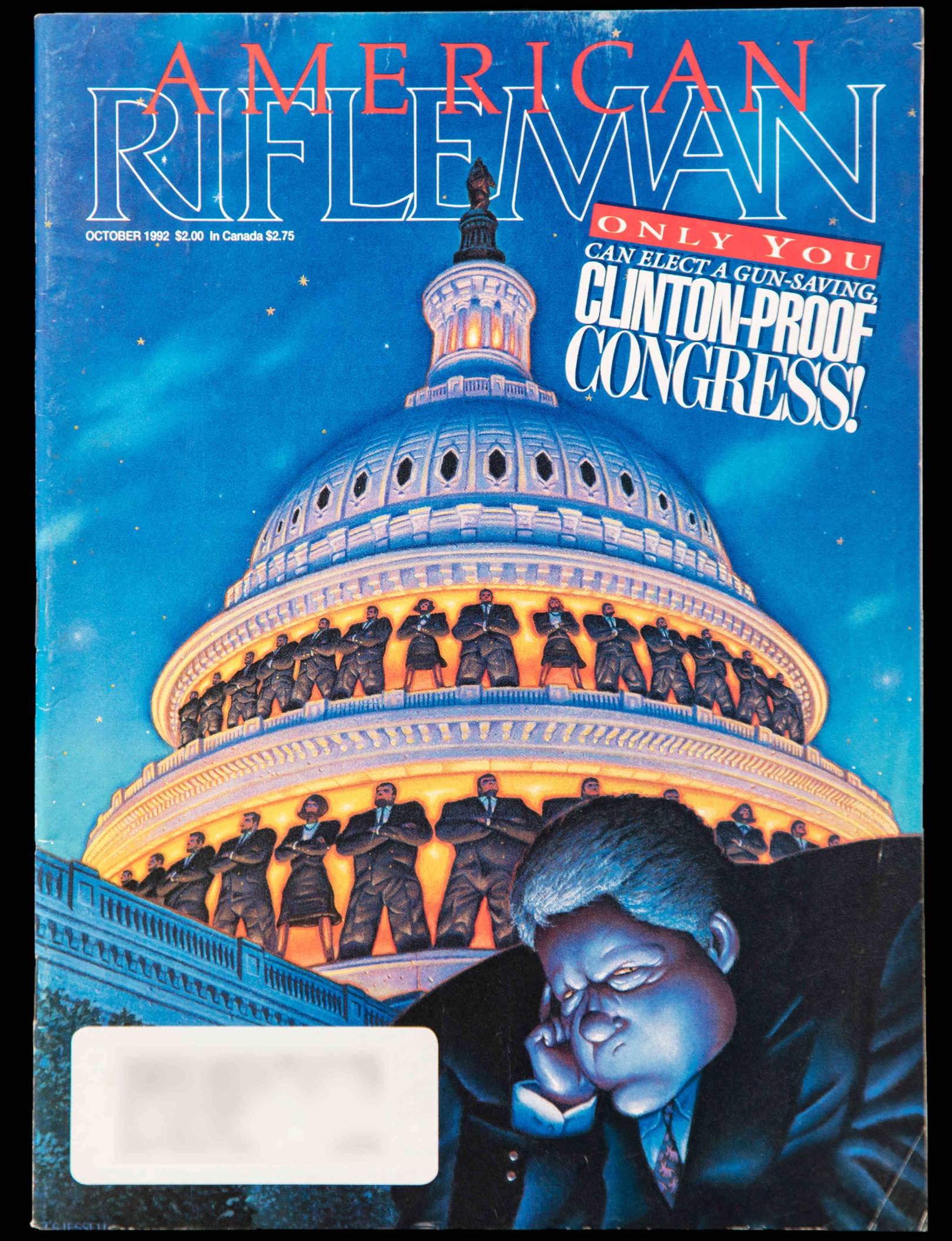

The organization bitterly opposed President Bill Clinton, who supported two major firearms safety laws. Before his election in 1992, it urged members to elect a “Clinton-proof Congress” to combat his legislative agenda.

October 1992

President Clinton signed the Brady Bill, which imposed background checks and a waiting period for purchasing firearms, and the N.R.A. was not pleased.

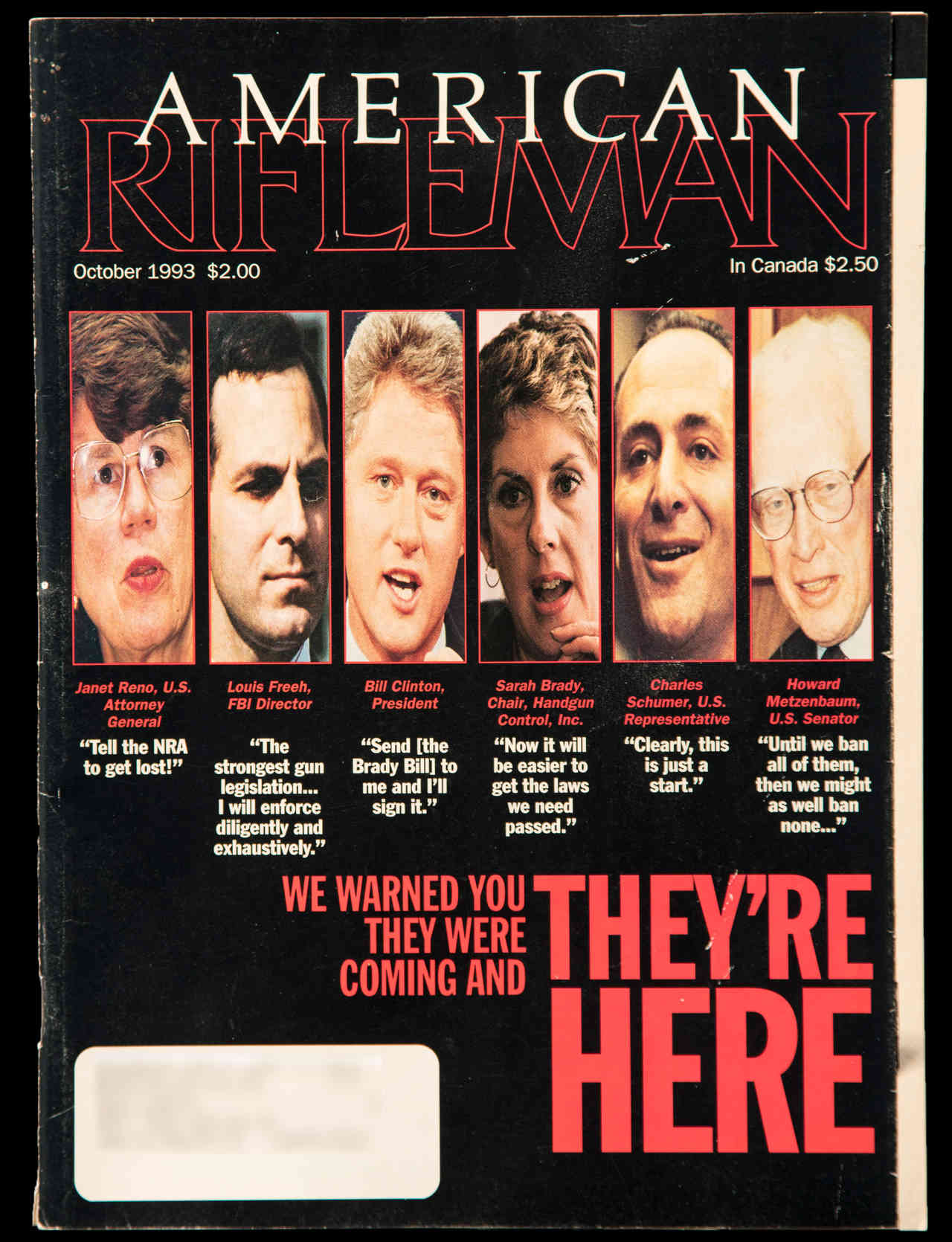

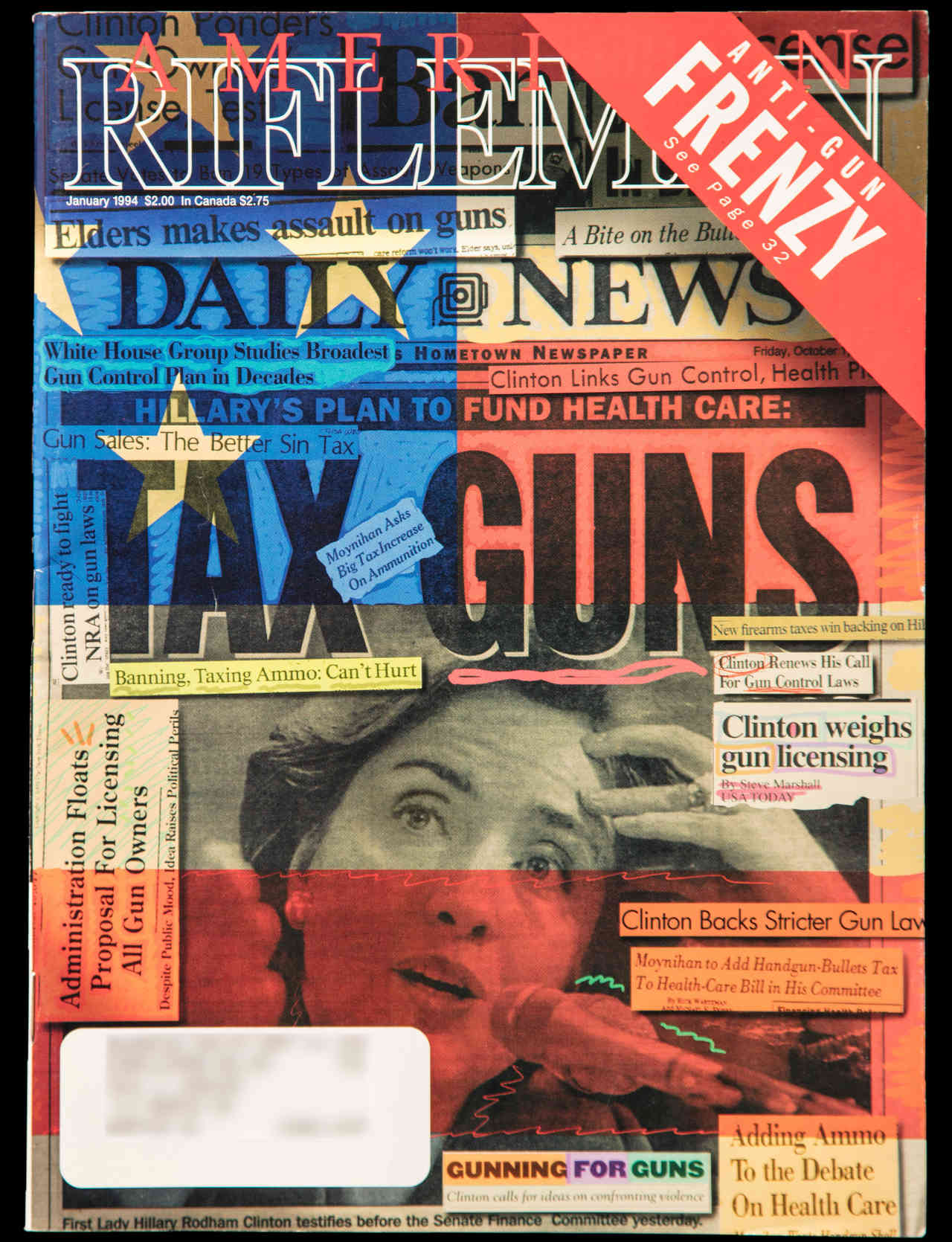

A 1993 cover offers a rogue’s gallery of “gun banners,” including Sarah Brady, a leading proponent of the bill. The magazine also targeted Hillary Clinton, the first lady at the time.

October 1993

January 1994

“The interesting tension is that the organization is simultaneously flag-waving and patriotic, and it also treats politicians and the state as though they are the actual enemy,” said Matthew Lacombe, a graduate student at Northwestern University who has studied The Rifleman’s editorials.

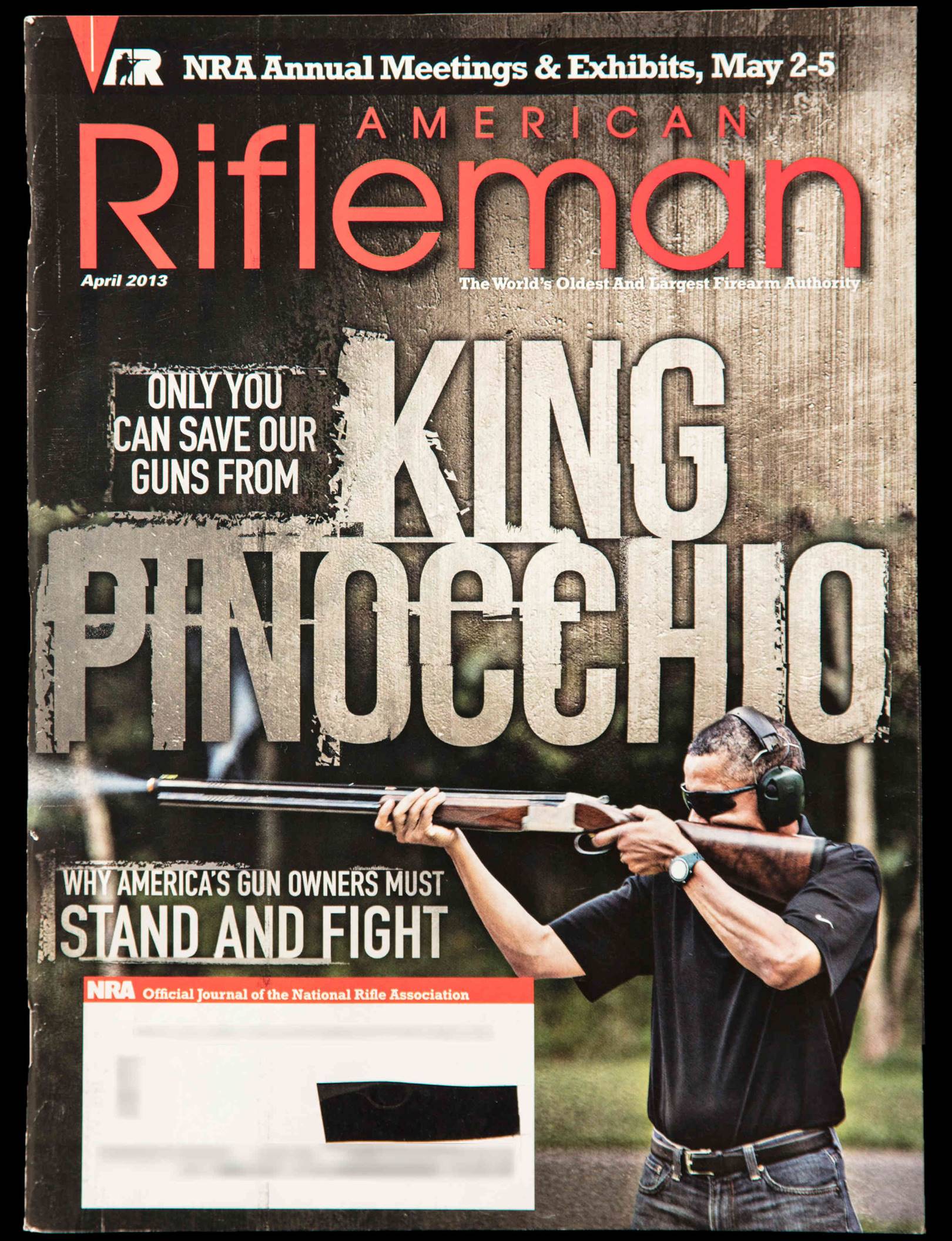

The magazine’s opposition to President Obama was particularly fierce. After he said he shot skeet as a hobby, the White House released this photo to back up his claim.

Pete Souza/The White House

The Rifleman repurposed the picture for its cover and dubbed Obama “King Pinocchio,” painting him as a false friend of gun owners.

April 2013

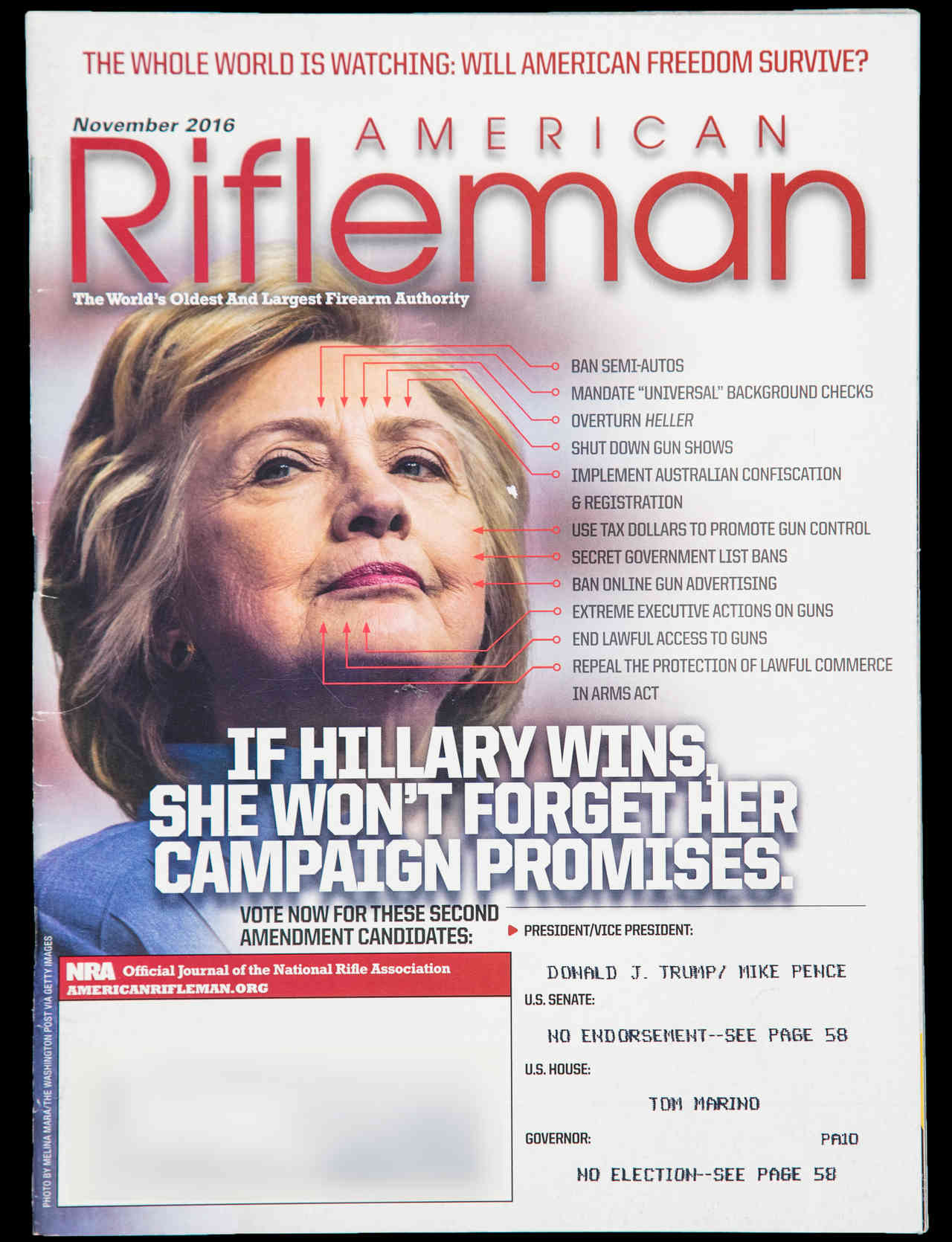

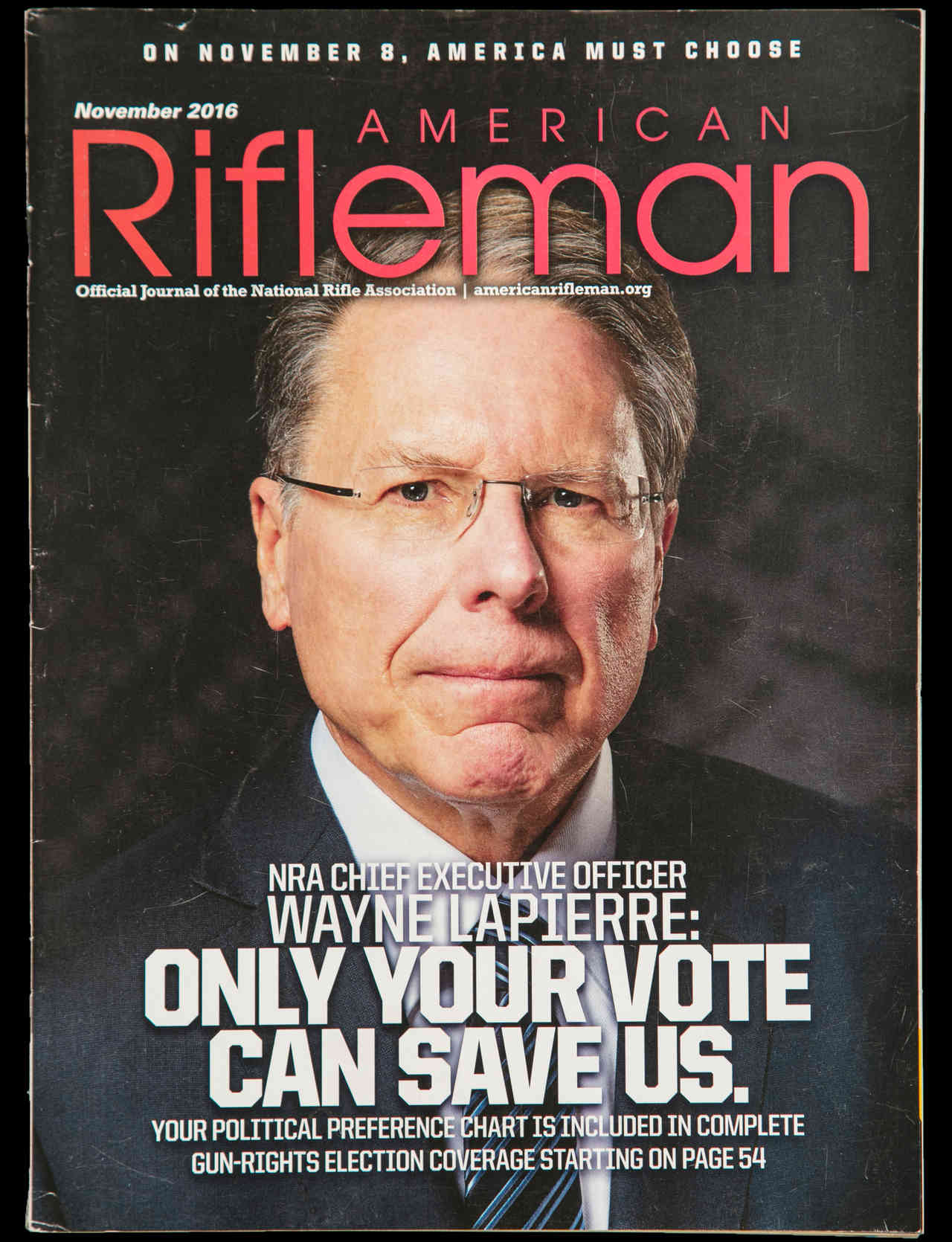

In the 2016 election, The Rifleman again attacked Hillary Clinton, then a presidential candidate, with an unflattering portrait. They later reused the tactic with Senator Chuck Schumer of New York.

November 2016

February 2017

If “gun-banning” politicians are the villains in The Rifleman’s world, then gun owners — and the N.R.A. itself — are the heroes.

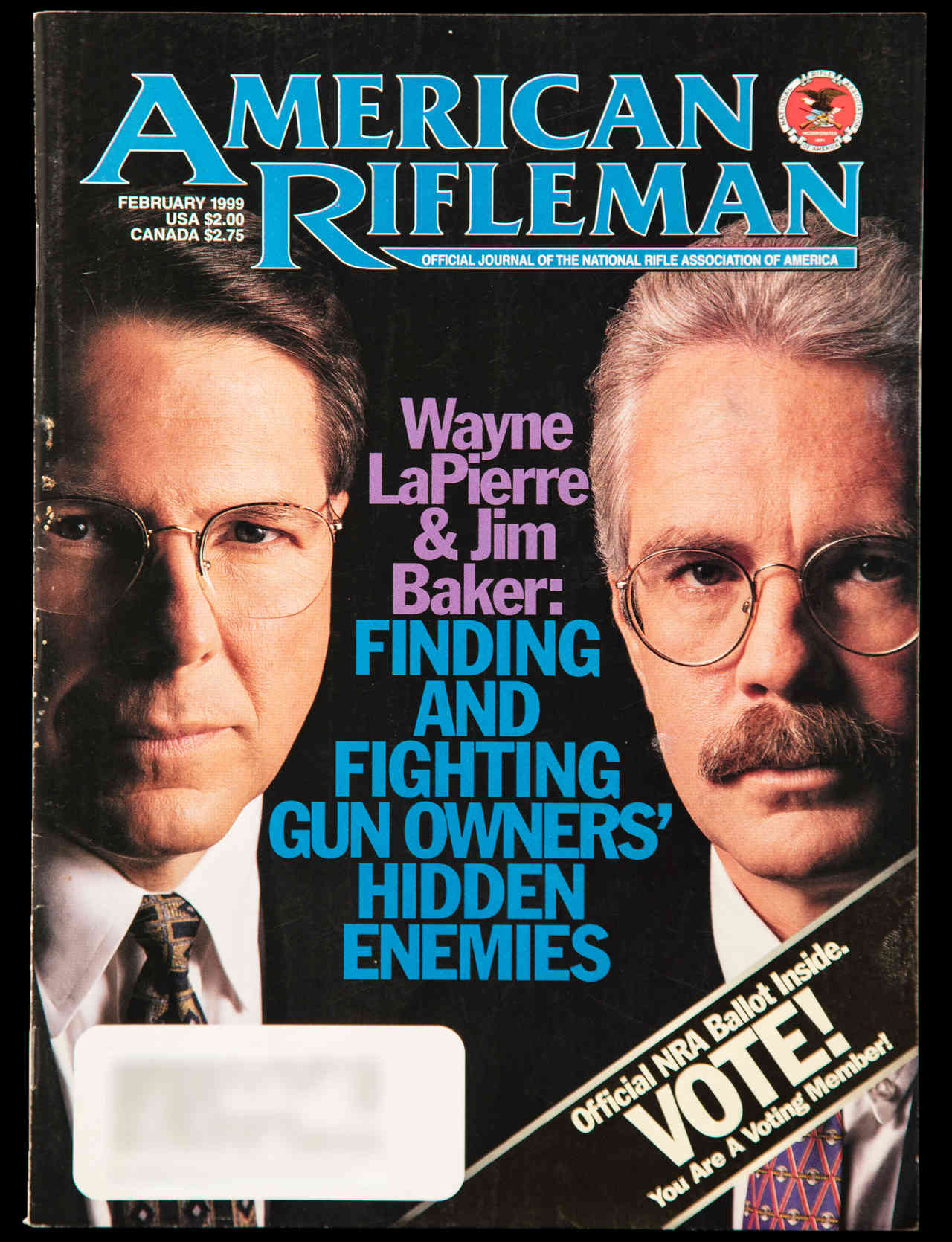

A 1999 cover lionizes two of the organization’s leaders fighting “hidden enemies.” Wayne LaPierre, the group’s executive vice president, appears again on a 2016 issue.

February 1999

November 2016

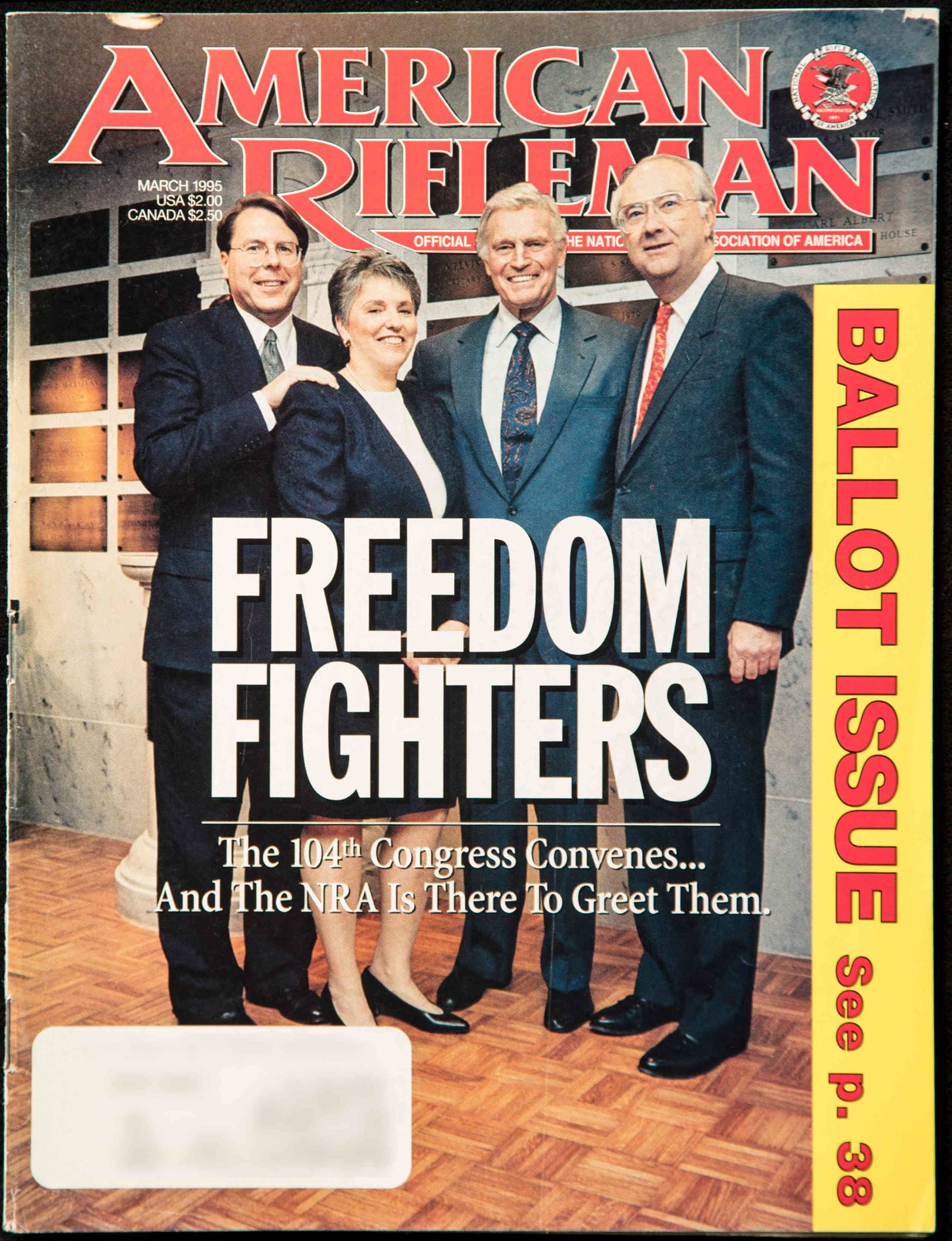

In 1995, Mr. LaPierre appeared alongside the actor Charlton Heston, who played the titular hero in the classic religious drama “Ben-Hur.”

March 1995

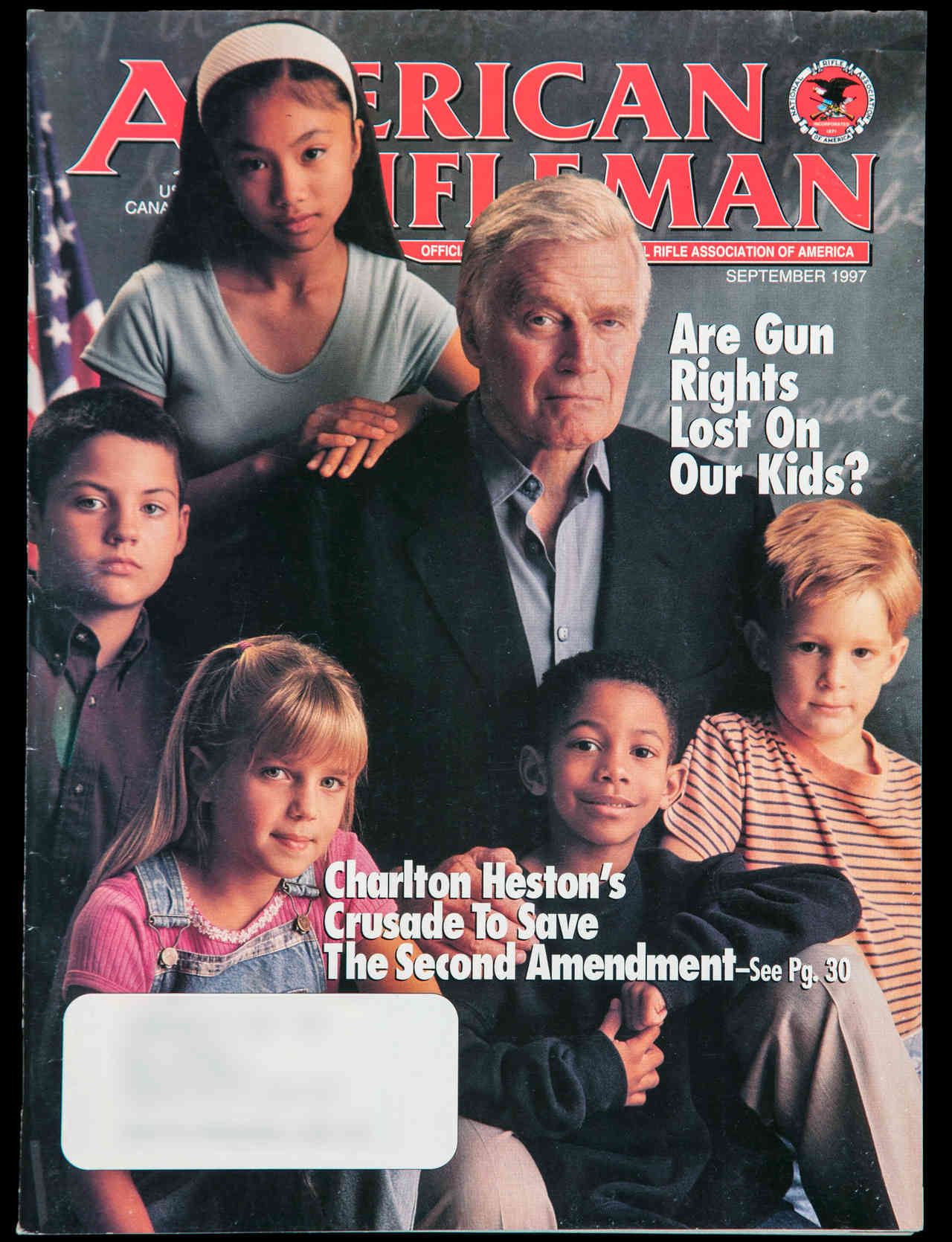

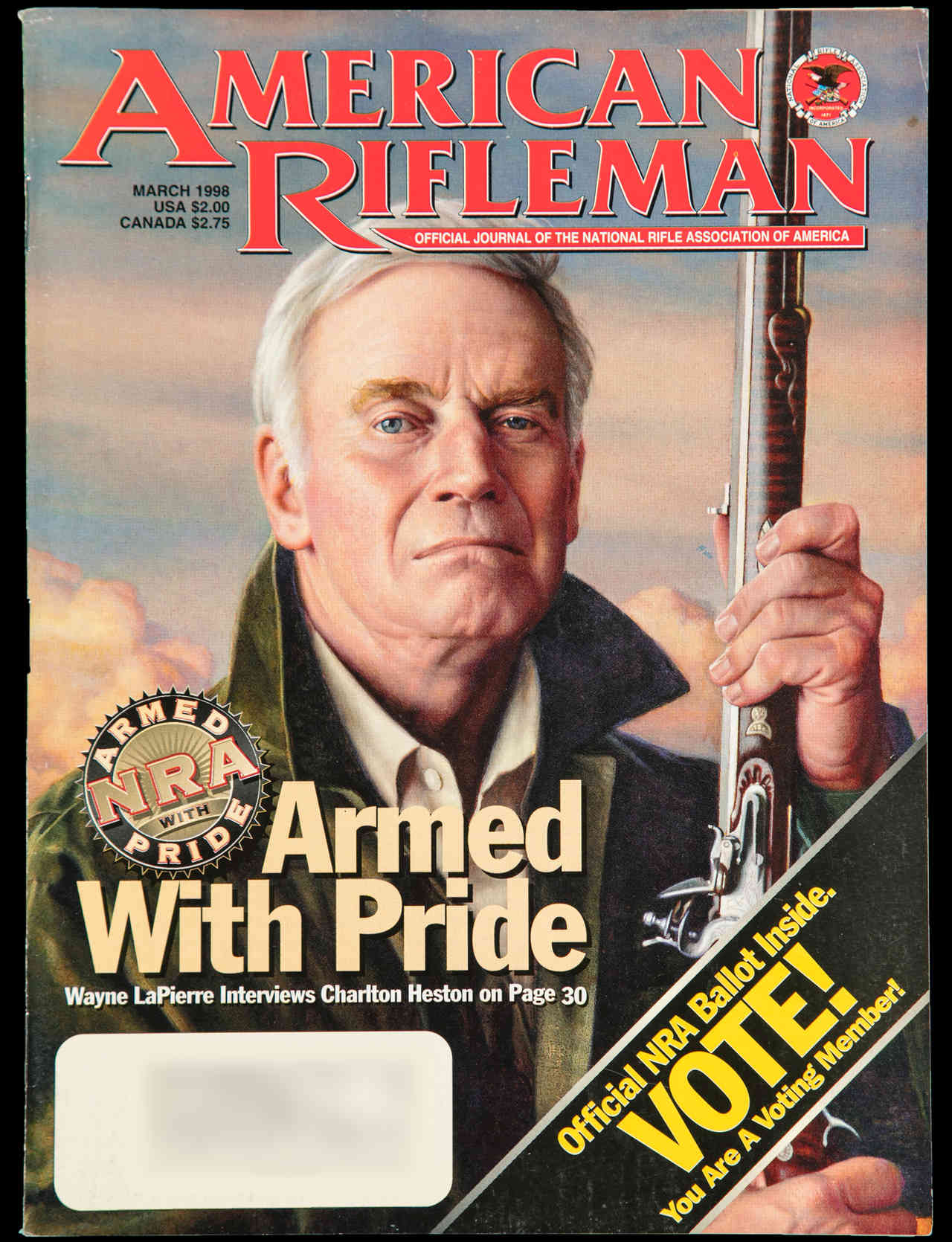

After that, Mr. Heston began cropping up frequently in The Rifleman. A 1997 cover doubles down on the religious allusion, labeling his pro-gun advocacy a “crusade.” In 1998, Mr. Heston became the N.R.A.’s president.

September 1997

March 1998

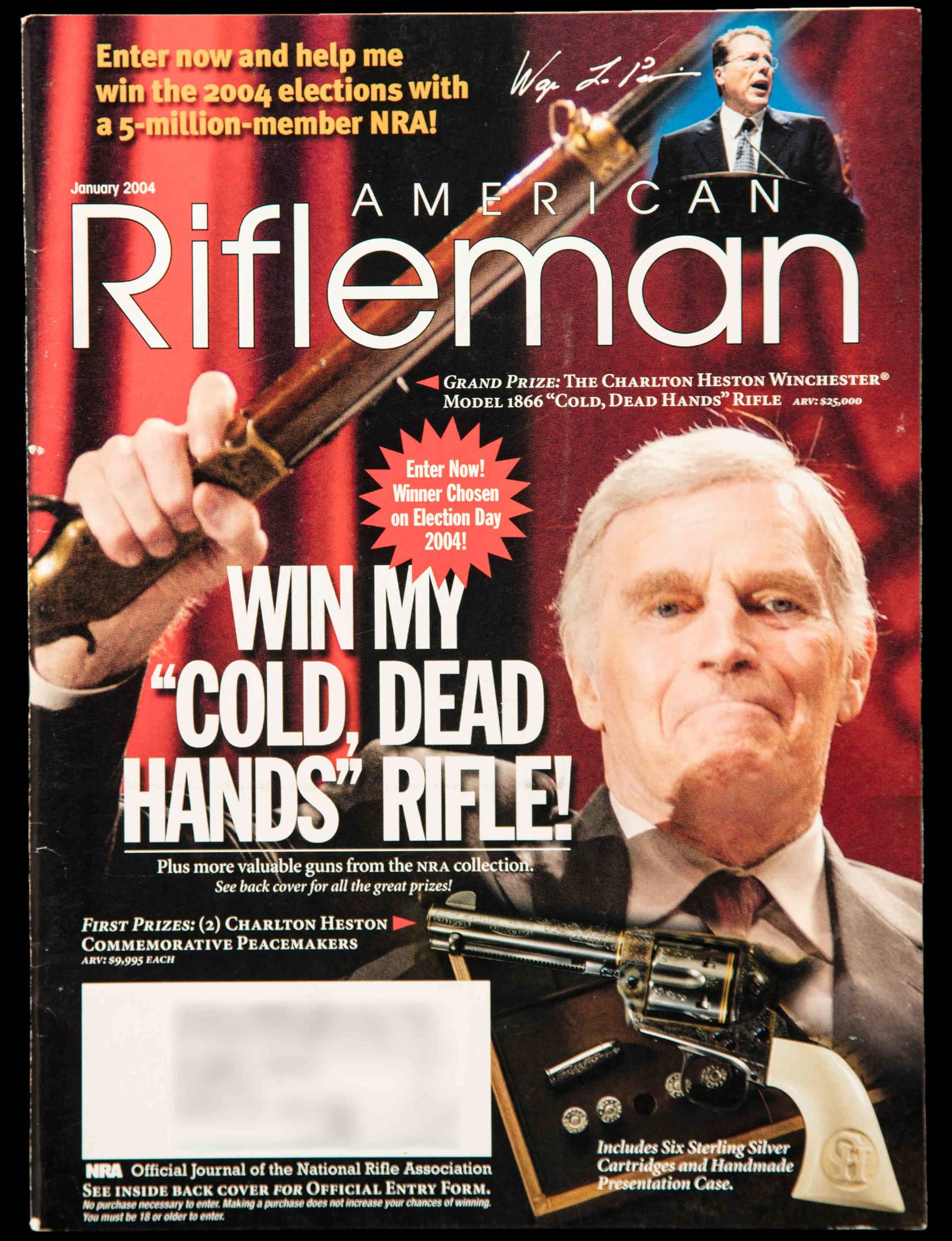

During the 2000 election, Mr. Heston raised a replica rifle and challenged the Democratic presidential nominee, Al Gore, to pry it from his “cold, dead hands.”

Charlton Heston at the 2000 N.R.A. annual meeting via 2Asupporters on YouTube

The phrase became a rallying cry. Later, the magazine offered the rifle as a prize to solicit donations and memberships.

January 2004

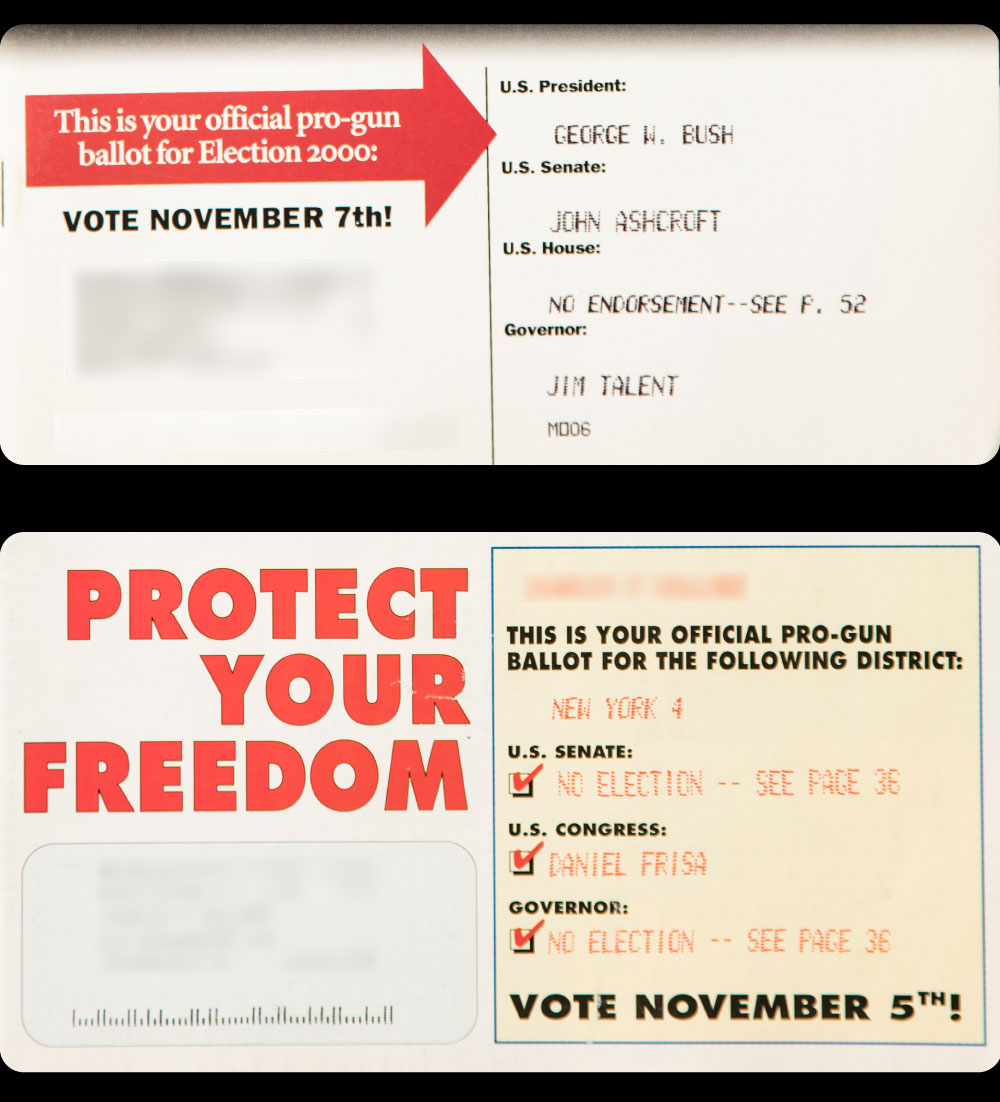

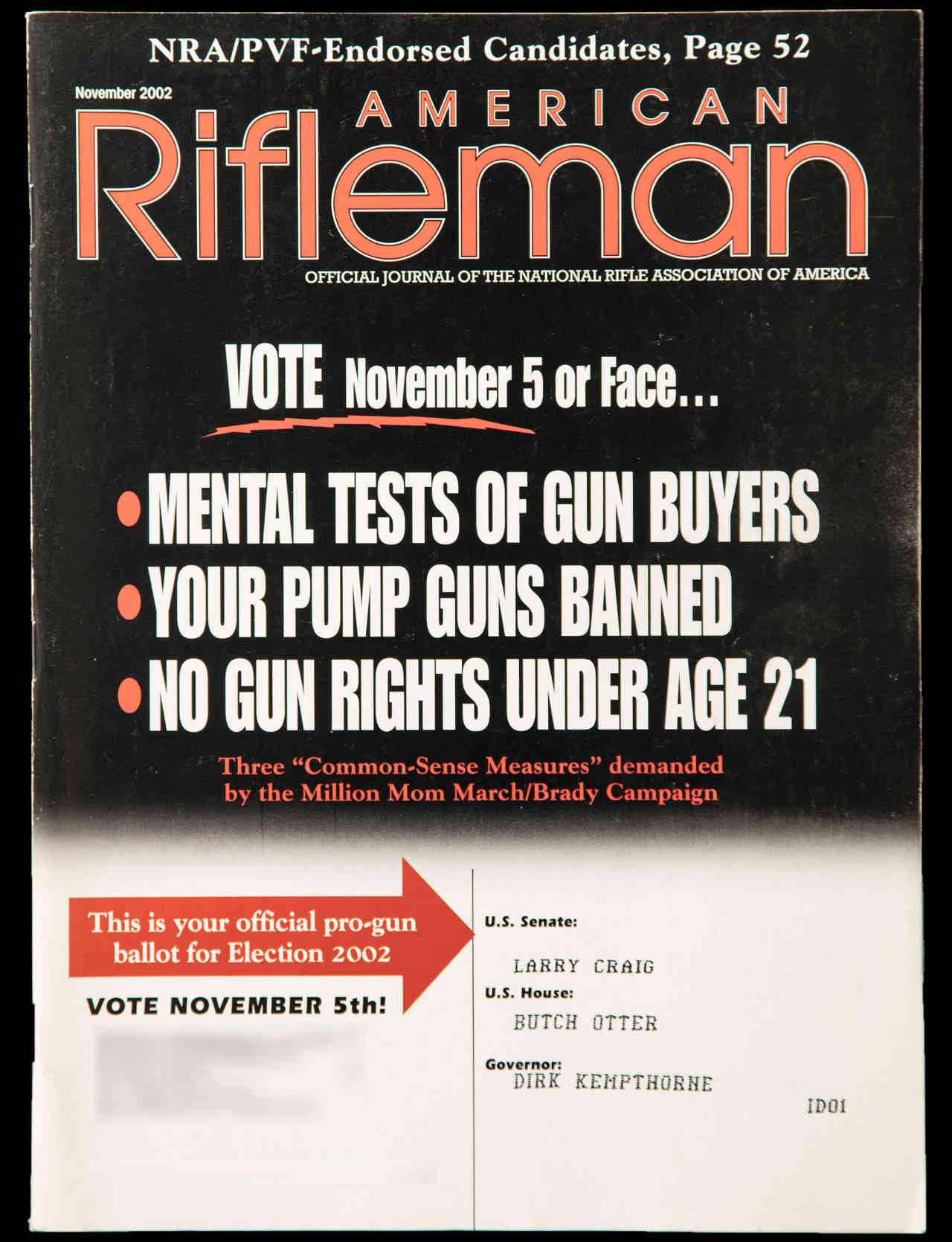

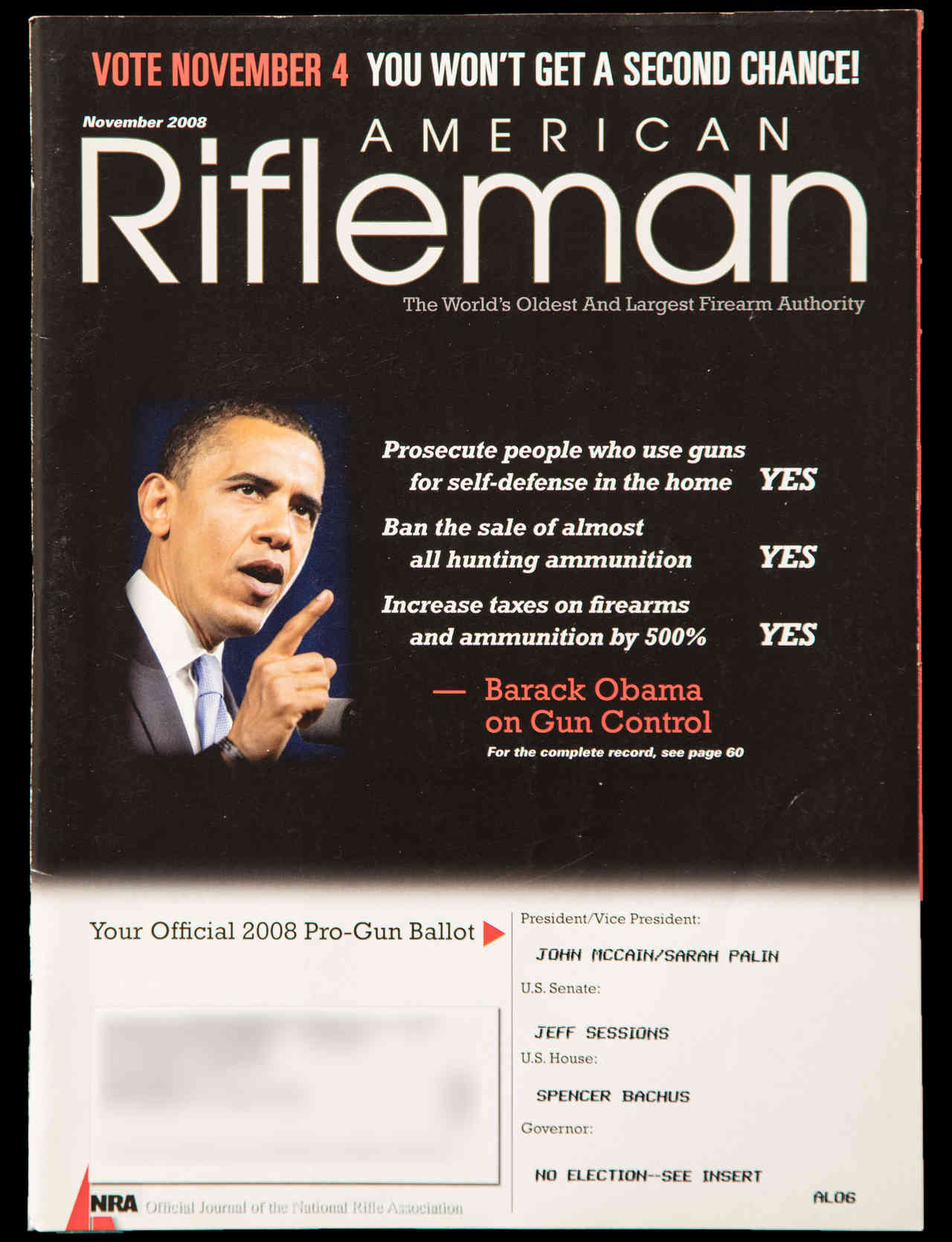

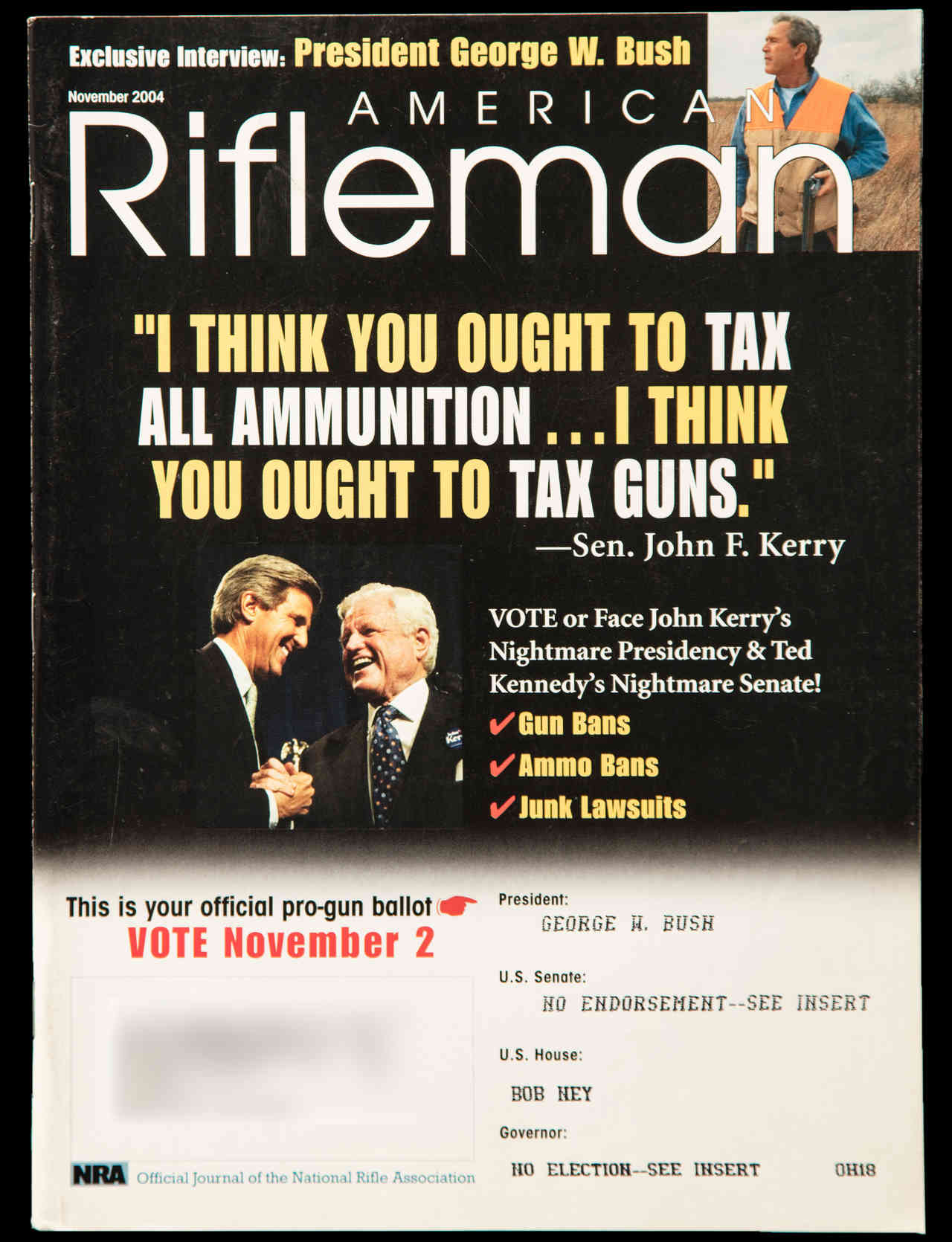

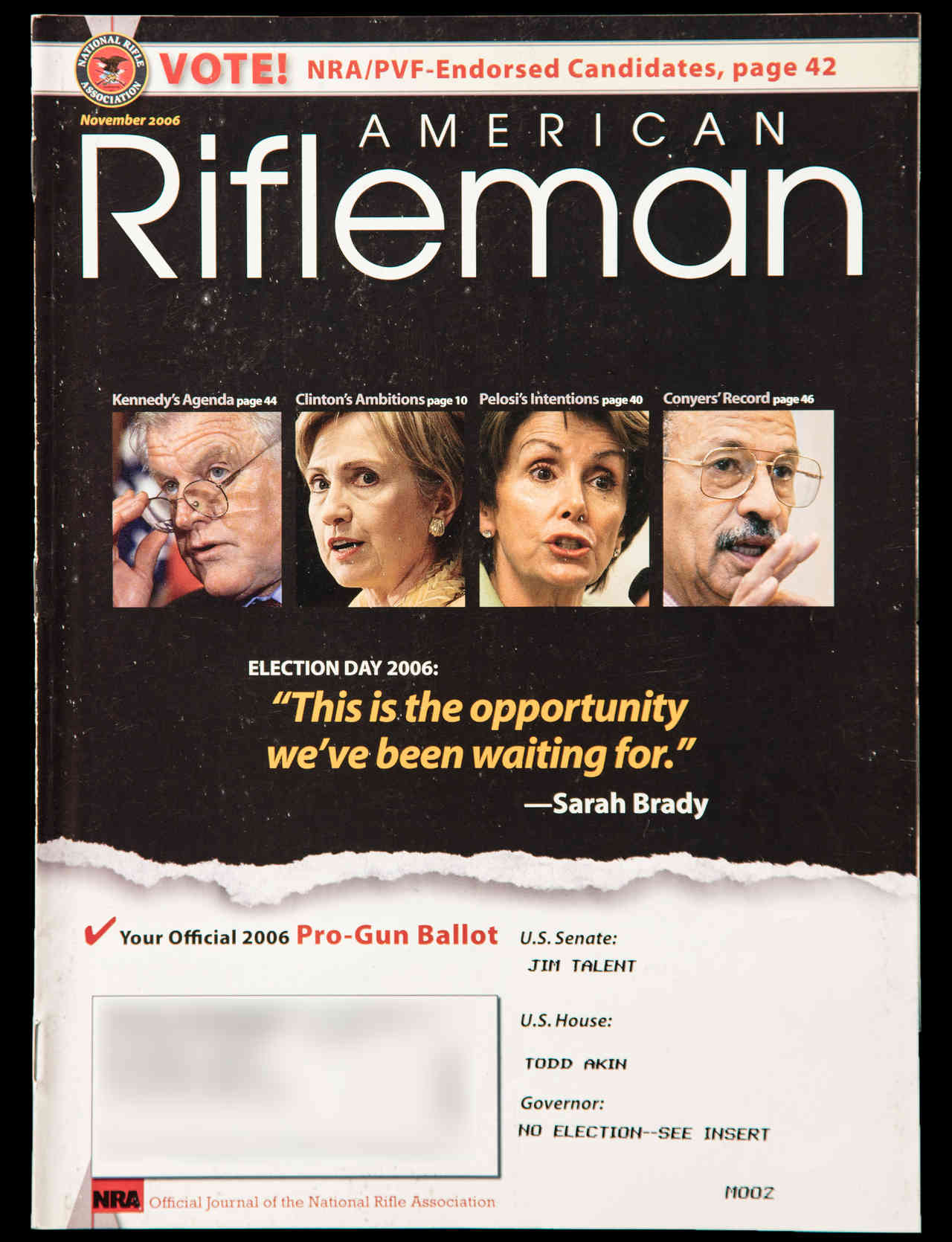

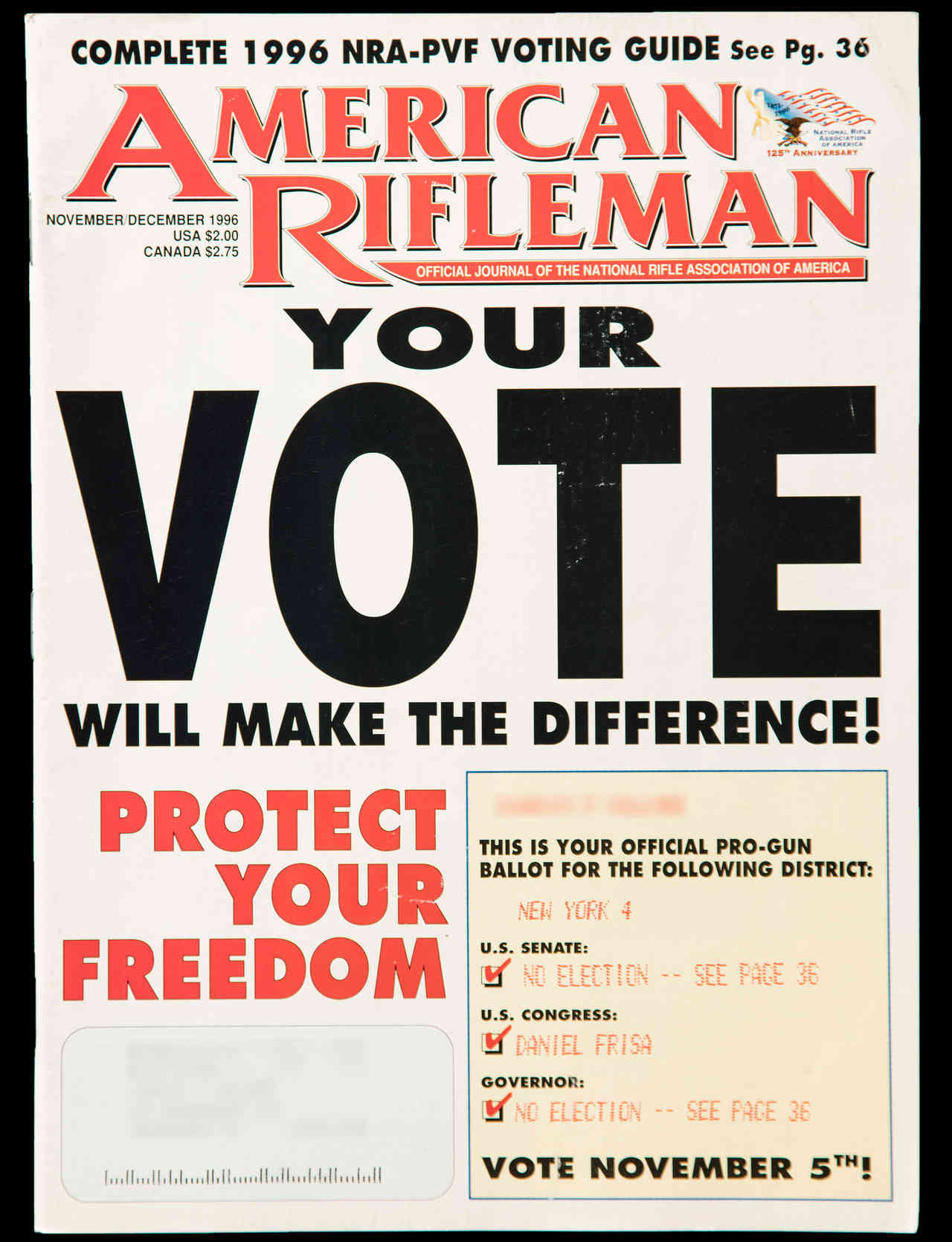

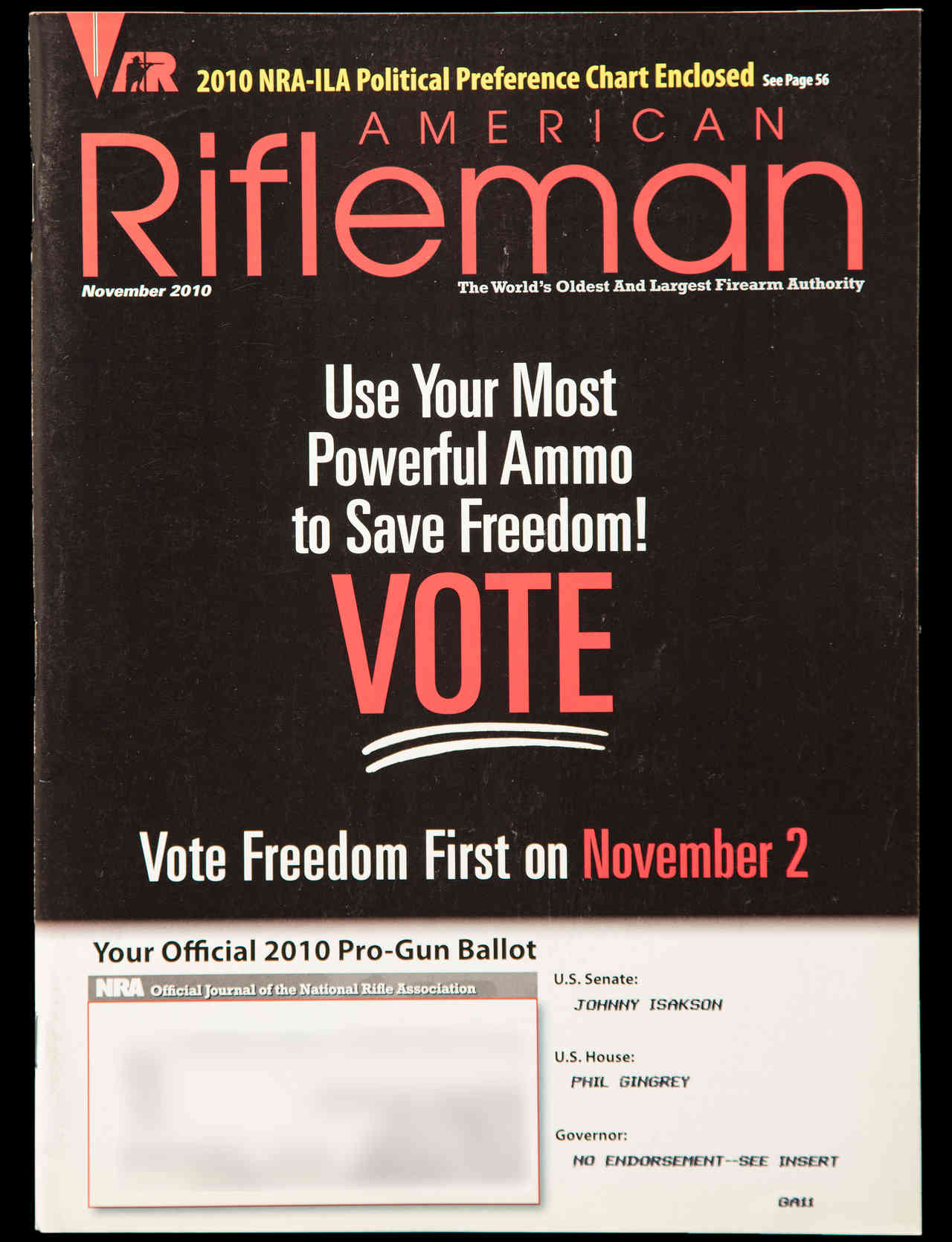

Since 1994, The Rifleman has printed N.R.A.-endorsed candidates at the bottom of its November cover each year, using subscribers’ information to personalize the “ballots” to their voting district.

The election issues pair these ballots with threats from outsiders whom the magazine suggests are acting “conspiratorially,” Mr. Lacombe at Northwestern said.

November 2002

November 2008

Covers have warned about “John Kerry’s Nightmare Presidency,” pointed to “Clinton’s Ambitions” and denounced “Pelosi’s Intentions.”

November 2004

November 2006

The language often addresses the reader directly.

“The number of times the word ‘you’ appears is remarkable,” Mr. Lacombe said. “Bad things will happen to you unless you take action.”

November 1996

November 2010

Recently, the group has found a friend in Mr. Trump, who has spoken at the 2017 and 2018 N.R.A. conventions. A 2017 cover highlights his meeting with Mr. LaPierre in the White House.

April 2017

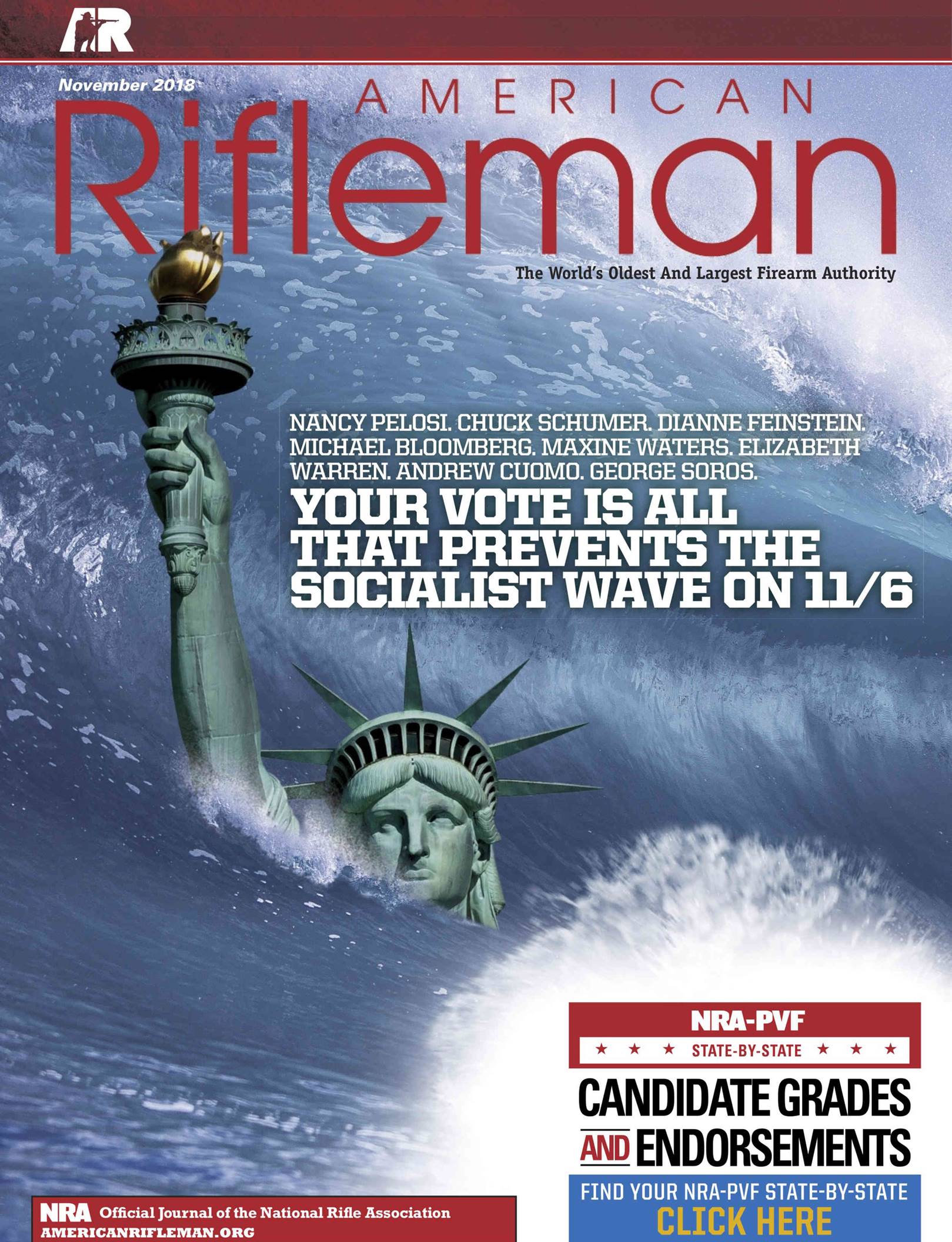

But despite a friendly administration, in November The Rifleman released an issue online that shows the Statue of Liberty drowning in a potential “socialist wave.”

November 2018

The group cannot “backtrack from the apocalyptic messaging,” Professor Spitzer at SUNY Cortland said. “They can’t say, ‘We won.’ They still need a villain, even though they hit the jackpot with Donald Trump.”

One of the reasons the United States has so many gun deaths is the N.R.A. and its extremist defense of handgun ownership, almost without limit. The evolution of the covers underscores that a group once about hunting and outdoor sports has transformed itself into a far-right political organization that simultaneously professes patriotism and promotes a virulent hostility to any government efforts to save the lives of Americans dying from guns at a rate of one every 15 minutes.

……………………………………….

New Yorker, October 19, 2015

Headline: Taking on the NRA

Byline: James Surowiecki

In the wake of the massacre at Umpqua Community College, in Oregon, Hillary Clinton promised that if she is elected President she will use executive power to make it harder for people to buy guns without background checks. Meanwhile, Ben Carson, one of the Republican Presidential candidates, said, “I never saw a body with bullet holes that was more devastating than taking the right to arm ourselves away.” The two responses could hardly have been more different, but both were testaments to the power of a single organization: the National Rifle Association. Clinton invoked executive action because the N.R.A. has made it unthinkable that a Republican-controlled Congress could pass meaningful gun-control legislation. Carson found it expedient to make his comment because the N.R.A. has shaped the public discourse around guns, in one of the most successful P.R. (or propaganda, depending on your perspective) campaigns of all time.

In many accounts, the power of the N.R.A. comes down to money. The organization has an annual operating budget of some quarter of a billion dollars, and between 2000 and 2010 it spent fifteen times as much on campaign contributions as gun-control advocates did. But money is less crucial than you’d think. The N.R.A.’s annual lobbying budget is around three million dollars, which is about a fifteenth of what, say, the National Association of Realtors spends. The N.R.A.’s biggest asset isn’t cash but the devotion of its members. Adam Winkler, a law professor at U.C.L.A. and the author of the 2011 book “Gunfight,” told me, “N.R.A. members are politically engaged and politically active. They call and write elected officials, they show up to vote, and they vote based on the gun issue.” In one revealing study, people who were in favor of permits for gun owners described themselves as more invested in the issue than gun-rights supporters did. Yet people in the latter group were four times as likely to have donated money and written a politician about the issue.

The N.R.A.’s ability to mobilize is a classic example of what the advertising guru David Ogilvy called the power of one “big idea.” Beginning in the nineteen-seventies, the N.R.A. relentlessly promoted the view that the right to own a gun is sacrosanct. Playing on fear of rising crime rates and distrust of government, it transformed the terms of the debate. As Ladd Everitt, of the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, told me, “Gun-control people were rattling off public-health statistics to make their case, while the N.R.A. was connecting gun rights to core American values like individualism and personal liberty.” The success of this strategy explains things that otherwise look anomalous, such as the refusal to be conciliatory even after killings that you’d think would be P.R. disasters. After the massacre of schoolchildren in Newtown, Connecticut, the N.R.A.’s C.E.O. sent a series of e-mails to his members warning them that anti-gun forces were going to use it to “ban your guns” and “destroy the Second Amendment.”

The idea that gun rights are perpetually under threat has been a staple of the N.R.A.’s message for the past four decades. Yet, for most of that period, the gun-control movement was disorganized and ineffective. Today, the landscape is changing. “Newtown really marked a major turning point in America’s gun debate,” Winkler said. “We’ve seen a completely new, reinvigorated gun-control movement, one that has much more grassroots support, and that’s now being backed by real money.” Michael Bloomberg’s Super PAC, Independence USA, has spent millions backing gun-control candidates, and he’s pledged fifty million dollars to the cause. Campaigners have become more effective in pushing for gun-control measures, particularly at the local and state level: in Washington State last year, a referendum to expand background checks got almost sixty per cent of the vote. There are even signs that the N.R.A.’s ability to make or break politicians could be waning; senators it has given F ratings have been reëlected in purple states. Indeed, Hillary Clinton’s embrace of gun control is telling: previously, Democratic Presidential candidates tended to shy away from the issue.

These shifts, plus the fact that demographics are not in the N.R.A.’s favor (Latino and urban voters mostly support gun control), might make it seem that the N.R.A.’s dominance is ebbing. But, if so, that has yet to show up in the numbers. A Pew survey last December found that a majority of Americans thought protecting gun rights was more important than gun control. Fifteen years before, the same poll found that sixty-six per cent of Americans thought that gun control mattered more. And last year, despite all the new money and the grassroots campaigns, states passed more laws expanding gun rights than restricting them.

What is true is that the N.R.A. at last has worthy opponents. The gun-control movement is far more pragmatic than it once was. When the N.R.A. took up the banner of gun rights, in the seventies, gun-control advocates were openly prohibitionist. (The Coalition to Stop Gun Violence was originally called the National Coalition to Ban Handguns.) Today, they’re respectful of gun owners and focused on screening and background checks. That’s a sensible strategy. It’s also an accommodation to the political reality that the N.R.A. created. ♦

Questions:

What strategies of influence did the NRA utilize? (Hint: use Ginsberg text here and use specific examples from the articles.) Explain why the NRA has been largely successful in achieving its aims.