Story Content

Historical collection shows impact Sac State activists had on Chicano movement

February 19, 2021

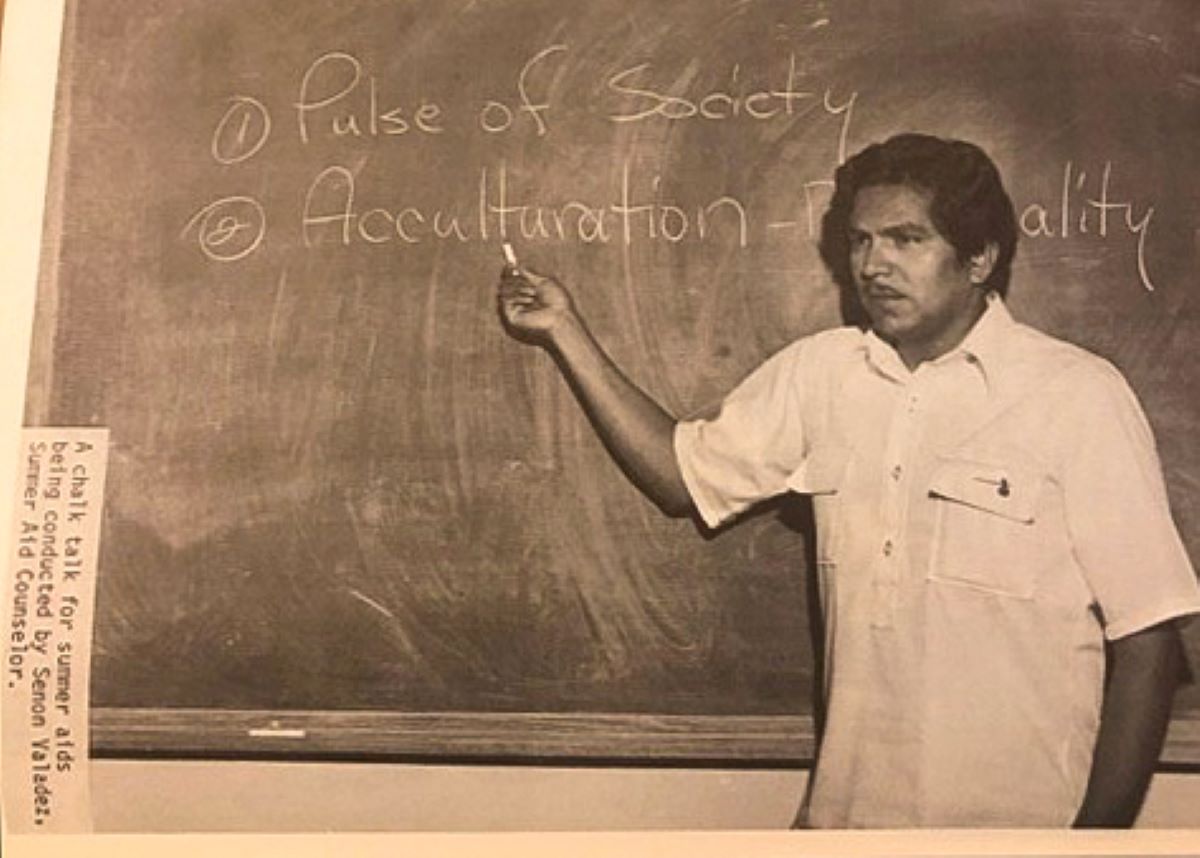

Senon Valadez, MA ’69 (Anthropology) knew time was running out to preserve the memories of women and men who took part in the Chicano civil rights movement while at Sacramento State in the 1960s and ’70s.

“I think we owed it to all of the people who got involved and made our journey in education and the situations in Sacramento far better than when we got here,” he said.

“The Sacramento Movimiento Chicano & Mexican American Education Project Collection” – oral histories of 98 mostly now-elderly activists – is a new acquisition by the University Library’s Gerth Special Collections and University Archives.

Expected to be accessible online later this year, it will serve as a primary resource for student and faculty researchers, as well as for scholars worldwide.

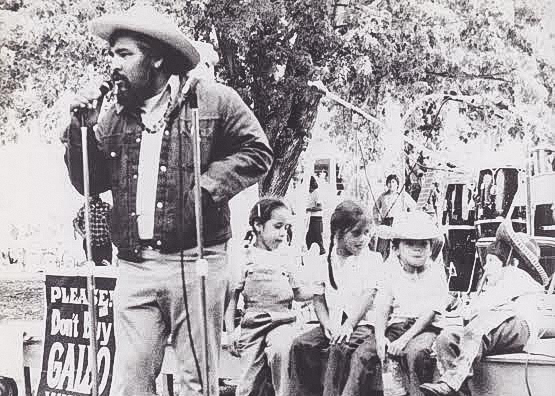

The 1960s were a time of civil rights activism across the country. In California, tireless effort and sacrifice by Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, and others in the United Farm Workers union improved working conditions for the state’s agriculture laborers, many of whom were Mexican nationals.

“It is so important to keep alive the Chicano movement’s history through this extensive oral history project with many activists who came out of Sacramento State,” said Paul F. Chavez, son of the renowned labor leader and president of the Cesar Chavez Foundation.

“The farmworkers’ struggle during the 1960s and ’70s was especially demanding and difficult. There were many daunting obstacles,” he said. “The presence and art of these Sacramento Chicanos, including members of the Royal Chicano Air Force, always uplifted my father and the farmworkers, gave them clarity and strength, and helped them carry on.”

A groundbreaking program

The Mexican American Education Project (MAEP) at what was then known as Sacramento State College was the nation’s first master’s degree program of its kind. In 1968, the college received $5.5 million in federal funding over five years to train teachers to help Mexican American children succeed in school.

Valadez, who attended Sac State as a MAEP student, grew up in a migrant laborers camp in the Salinas Valley. His parents were farmworkers and spoke only Spanish with their children. He struggled in school because of the language barrier. As a teen, he faced discrimination whenever he applied for part-time work. He remembers being told again and again, “Sorry, we aren’t hiring,” only to see the jobs go to white peers.

“I wanted to pay homage to Sacramento and those who helped build me as a person, politicized me, educated me. ... It’s a place folks don’t tend to think of as a hub for activism, but I was very much inspired by that generation. I knew there was a story to be told.” - Lorena V. Márquez

But Valadez persevered, mastering English, receiving good grades, and earning his undergraduate degree before taking a teaching position at a Union City elementary school.

In 1968, he was among the first schoolteachers recruited for MAEP, which was housed in Sacramento State’s Department of Anthropology.

Valadez earned his master’s degree in 1969 and stayed on to teach Anthropology until his retirement in 2003. A few years later, as he recovered from cancer, he had time to reflect on the struggles he endured as a brown-skinned man living in California. He considered writing his autobiography.

He shelved that idea, though, to embark on a more ambitious effort that would allow many more people to tell their stories.

‘The history of a movement’

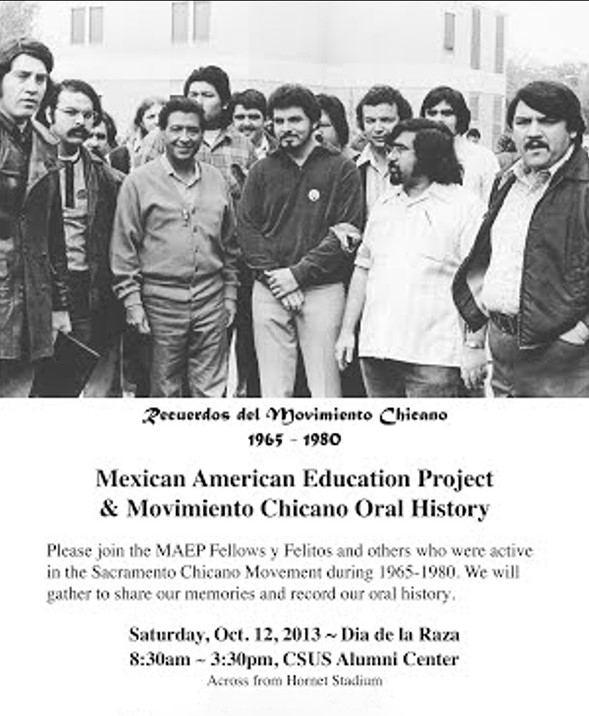

In 2013, Valadez and his friend Sam Rios, the late professor emeritus of Anthropology and Ethnic Studies, invited alumni who were a part of the Chicano movement to a reunion on campus, where they proposed using oral histories to document their shared and unique experiences.

And so, “The Sacramento Movimiento Chicano and Mexican American Education Project Collection” was born.

“This is an amazing first-person telling of the Chicana/o movement in Sacramento,” said Library Dean Amy Kautzman. “The Library puts a heavy emphasis on capturing local history, be it social, political, the arts, etc. This collection shows the ‘power of the people’ in changing social norms and working toward a more equal union.

“It’s the history of a movement,” she said. “It is evidence of how regular people, our fellow Sacramentans, changed history and improved life for their current and future community.”

Valadez enlisted the help of Lorena V. Márquez ’99 (History, Spanish), MA ’02 (History), whom he had met when she interviewed him for her dissertation at UC San Diego.

Márquez, an assistant professor of Chicana/o Studies at UC Davis, trained undergraduate students in her Qualitative Methodology class in the art of interviewing. They videotaped the stories of 98 activists in 2014 and 2015, with most meetings being held in the Sacramento City College library.

A later group of UC Davis students transcribed the interviews, which Márquez is proofreading before they become a part of the project housed at Sac State.

“Every story is unique,” she said. “As a historian, learning about the racism that a lot of these folks experienced – the psychological scars, the emotional trauma of being laughed at and shamed for speaking Spanish – is powerful.

“And then how this generation fought through the inferiority complex that was ingrained in them during their K-12 education and really shattering those images, those low expectations of them, and going to college.”

The movement’s lasting legacy

The stories also demonstrate the way higher education shaped young minds before these individuals returned to their communities and made significant changes, Márquez said. Men and women who were Sac State students in the 1960s went on to launch such community organizations as Mi Familia Counseling Center, which still exists, and ambitious prison outreach and reform programs.

During this period, as well, Sacramento State faculty members José Montoya and Esteban Villa founded the influential Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF) art collective at the University. A collection of more than 170 silkscreen posters related to farmworkers’ rights, educational programs, community events, and Chicano history is housed in Special Collections and University Archives.

This generation also helped elect Joe Serna Jr. as Sacramento’s first Latino mayor in 1992. He had been a longtime professor of Government at Sac State.

“That’s the kind of momentum that was really garnished in Sacramento during this time,” said Márquez, the only member of her family to attend college. She arrived at Sac State in 1994 as a freshman, supported by the College Assistance Migrant Program and Educational Opportunity Program.

Her first book, La Gente: Struggles for Empowerment and Community Self-Determination in Sacramento, recently was published by the University of Arizona Press.

“I wanted to pay homage to Sacramento and those who helped build me as a person, politicized me, educated me, and made me into a young, independent strong woman,” she said. “It’s a place folks don’t tend to think of as a hub for activism, but I was very much inspired by that generation. I knew there was a story to be told.”

For Márquez, the oral history project is a labor of love, dedicated to the people who came before her and made a difference in the lives of many. She and all involved in creating the project gave their time pro bono.

“I knew if we stuck with it that it would be an impressive collection,” she said. “From my understanding, there is no other collection on the Chicano movement era like it, in terms of its size.”

VIDEO: Terezita Romo on what the Chicano movement made possible

Media Resources

Faculty/Staff Resources

Looking for a Faculty Expert?

Contact University Communications

(916) 217-8366

communications@csus.edu