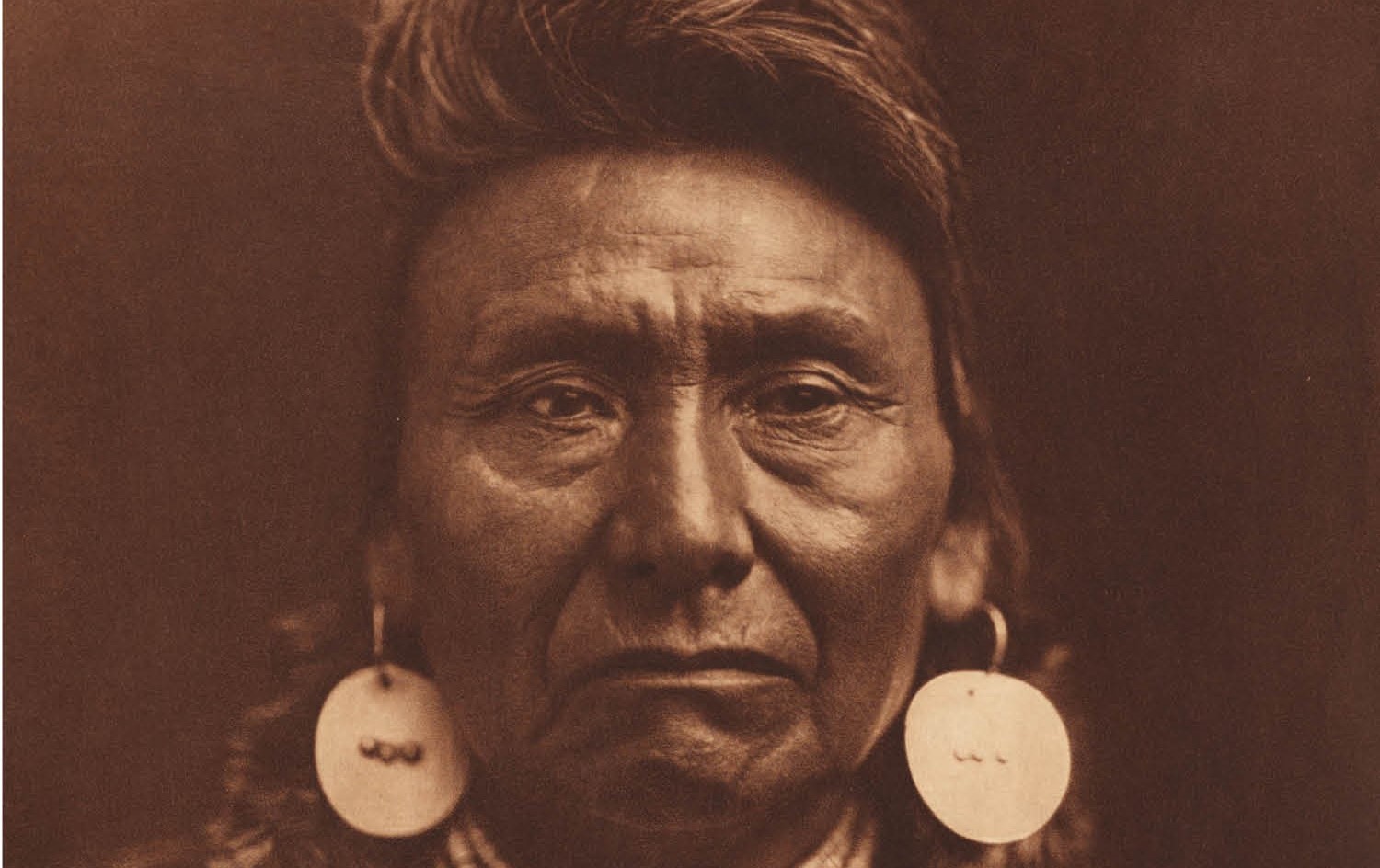

Chief Joseph, one of American history's great figures, is among the many native people whose image was captured by Edward Curtis. Many of Curtis' pictures are on display in the University Library Gallery. (Special to Sacramento State)

Chief Joseph, one of American history's great figures, is among the many native people whose image was captured by Edward Curtis. Many of Curtis' pictures are on display in the University Library Gallery. (Special to Sacramento State)Edward S. Curtis was a Seattle studio photographer who had a loyal following of wealthy clients in the late 1800s. He gave up his comfortable existence to spend 30 arduous years in the field, photographing Native Americans and their disappearing way of life.

Curtis had financial backing for the project from New York millionaire banker J.P. Morgan, but he never took a salary for his work and died nearly penniless at age 84 in 1952.

He once said his intention was “to form a comprehensive and permanent record of all the important tribes of the United States and Alaska that still retain, to a considerable degree, their … customs and traditions."

Sacramento State’s University Library Gallery is honoring Curtis on the 150th anniversary of his 1868 birth with the exhibit The Shadow Catcher: Edward S. Curtis and the Making of the North American Indian (1907-1930). The 47 sepia-toned photogravures hanging in the gallery through Dec. 14 are on loan from the California State Library.

“Curtis realized that their culture was rapidly being transformed by the white man moving onto their land,” said exhibit curator Gary F. Kurutz, the State Library’s former director of Special Collections. “Native Americans were learning to adapt as their tribal boundaries were wiped out. And Curtis knew that when the elders died, their history went with them.”

A companion exhibit to the Curtis show is Witnessing Resurgence: Portraits of Resilience, a collection of contemporary Native American photographs by Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie, professor of Native American studies at UC Davis.

Free lectures related to the two exhibits are scheduled for Thursday, Dec. 6, in the Library Gallery: Kirk Rudy, director of the Edward S. Curtis Gallery in McCloud, Calif., will share stories of the legendary photographer known as the "Shadow Catcher” at 1 p.m.; and Tsinhnahjinnie's talk will follow at 3 p.m.

The 47 Curtis photogravures – exquisitely detailed photographic prints produced from the photographer’s original copper plates – were selected from The North American Indian, his epic, 40-volume collection of images and writings. President Theodore Roosevelt, who introduced Curtis to financier Morgan, wrote the foreword to The North American Indian.

“It ranks as one of the most beautiful, complex, and costly publications ever created in the United States,” Kurutz said.

The volumes were published one by one over 23 years, at a cost of $1.2 million.

Curtis sold his work by subscription, soliciting potential customers as he traveled thousands of miles across the United States and into Alaska to photograph what he called the “vanishing race.” He would publish 222 sets of The North American Indian, fewer than the 500 he originally had planned. The California State Library was his 69th subscriber.

On May 9, 1910, State Librarian James L. Gillis agreed to pay $160 for each volume as it was published, for a total cost of $3,200. A complete set of The North American Indian brought $1.44 million at auction in 2012.

“Curtis hoped to garner many more subscribers, but not surprisingly, many would-be buyers were either skeptical or canceled their subscriptions because of the length of time in production,” Kurutz said. “Fortunately, the State Library patiently waited the 23 years for Volume 20 to be issued. Anyone seeing his dramatic images would have to agree that the wait was well worth it.”

One of the most stunning photogravures in the Library Gallery exhibit is the portrait of Chief Joseph, the Nez Percé leader, taken in 1903. Other highlights include The Offering (1925, San Ildefonso) and The Blanket Weaver (1904, Navajo.)

Curtis produced 40,000 images of 80 tribes, showing their daily life and customs, though he has been criticized in some circles for staging some of his photographs. Such criticism, however, does not dim his accomplishment in showing important parts of Indian life.

“He documented Native Americans. If he hadn’t, we wouldn’t have the visual history that we do,” said Phil Hitchcock, director of Sac State’s Library Gallery. – Dixie Reid